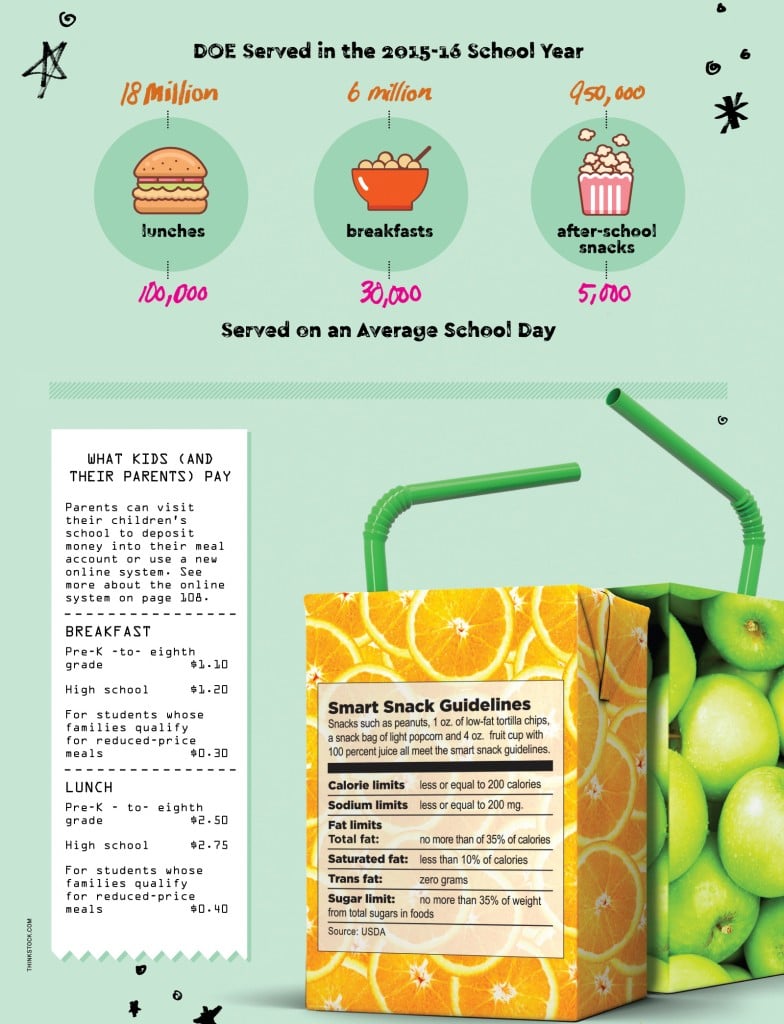

24 Million Meals a Year

I have mostly fond memories of eating during my eight years in the public school system. I’m especially sentimental about the saimin and oven-roasted chicken I ate during lunches at Niu Valley Middle School. In fact, I ate more than 400 meals at three cafeterias, but students who eat two meals each school day from kindergarten through grade 12 would consume almost 5,000 meals during their school years. The steps leading to those meals is quite a process and it all starts with planning the menus and deciding what kids will be scarfing down every school day.

MEAL PLANNING

Antonio Omphroy, now a junior at Kaiser High School, says that when he was younger, his favorite lunch was the fish nuggets with tartar sauce served at Mililani Mauka Elementary School. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

The menus originate with the statewide menu committee, which consists of one school food service manager from each of the three Neighbor Island counties – Kauai, Maui and Hawaii Island – and one each from the four Oahu school districts: Honolulu, Central, Leeward and Windward.

Rayburn Awaa Lincoln, Kaimuki High School’s cafeteria manager, is serving his first year on the menu committee team. He says the committee starts each year by looking at the previous year’s menu and at sales. Yes, it’s true, the menu planners do care about whether students like the meals or not, so they study sales from previous years to see what students bought or didn’t buy.

In addition to student and staff feedback, the menu committee also considers nutrition, vendor bidding and product availability. And food shows are sometimes held at schools to collect feedback, with a member of the menu committee there to hear student comments after a taste test.

“We try as much as possible to get the best product as possible at a very reasonable cost to serve to the students,” Lincoln says.

While I was in school, just about everyone complained about school lunches. And, from conversations I have had since, times have not changed. But there are some who like the food. From kindergarten to fifth grade, Antonio Omphroy attended Mililani Ike and Mililani Mauka elementary schools, where he says the tastiest meals were the fish nuggets with tartar sauce served at Mililani Mauka.

After three years at Mid-Pacific Institute, he is back in public school for high school, and is a junior at Kaiser High School, where he says some school lunches are enjoyable.

“It’s a good portion and I’m satisfied with the entree and fruits. I like that you also get snacks,” Omphroy says, who adds that he’s a baseball player with a big appetite. However, he does wish there were more vegetable options to choose from.

INGREDIENTS

Lanikai School has both a greenhouse (below) and an outdoor garden and farm (top, at right), created with help from the Kokua Hawaii Foundation. Below right: Rayburn Awaa Lincoln, Kaimuki High School’s cafeteria manager, and his colleagues prepare bread rolls for the next day’s meals. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

Forty percent of fruits, vegetables and meats in school lunches are procured locally, with the rest coming from the Mainland and Latin America, says Lindsay Chambers, communications specialist at the Hawaii Department of Education. She says the DOE is striving to increase those numbers under the National Farm to School Network, which is led in Hawaii by Lt. Gov. Shan Tsutsui.

However, Farm to School coordinator Robyn Pfahl with the state Department of Agriculture says the actual percentage of local products on school lunches is a lot less than 40 percent. She works with nonprofits and school cafeteria managers to improve the FTS pilot project, which began in Hawaii in 2015.

“It’s my job to get more local food in our school lunches. But, right now, it’s nowhere near 40 percent, I can guarantee it,” Pfahl says.

Another perspective comes from Brandon Lee, policy and public-private partnership associate at Ulupono Initiative, an investment firm founded by Pierre and Pam Omidyar and working to help produce more locally produced food for Hawaii residents. He says a Kohala school on Hawaii Island was selected to be sampled for baseline data and reported preliminary numbers.

He says only 1.5 percent of food, excluding milk products, were procured locally while the number rises to 20 percent with milk products because of a dairy farm on the island.

“It’s probable that numbers will be similar on other islands,” Lee says.

Aside from procurement, the initiative also encourages school gardens, where students learn about fresh vegetables by planting, caring for and harvesting their own.

Natalie McKinney, executive director of Kokua Hawaii Foundation, a nonprofit that supports environmental education, says two-thirds of the DOE schools – about 170 – have school farms. “We wanted to get more local on the plate,” McKinney says.

One participating school is Waikiki Elementary, where Hoku is a fifth grader who enjoys eating salads at home while learning how to compost and garden at school.

Tara, Hoku’s mother, says she sets a high bar for nutrition and hopes vegetables from the garden can one day be used in school lunches. “It’ll be tricky, but it would be nice to bring it from the garden,” Tara says.

Frozen and dry products are delivered to schools twice a week, while produce and milk are delivered more frequently to ensure freshness.

Albert Scales, the supervisor at the DOE’s School Food Services Branch, has been with the DOE since August 2014. Before that, he was in the military for 20 years, where he served in food management positions. He has many roles at the DOE: creating specifications for all procurements, evaluating bids, managing equipment and food contracts, and conducting fiscal reviews. The procurement and contract branch collects bids from vendors who meet the requirements and the contracts are awarded to the lowest bidders, Chambers says.

For example, Y Hata & Co. delivers 31 items such as cinnamon buns, vegetable oil and beef stew to schools statewide for breakfasts and lunches under a contract from July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017.

CAFETERIA PROCESS

Rayburn Awaa Lincoln, Kaimuki High School’s cafeteria manager, says he asks himself this question every day: How can I make the food better within the nutritional guidelines, cost restraints and other parameters I’m locked into? Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

The set menu each school year is a series of three-week cycles, each consisting of 15 different meals. Cafeteria managers can change and shuffle meals throughout the year to create diversity, though changes must follow nutrition guidelines.

Cafeteria managers take care of purchasing, inventory and a daily production sheet. Of the 256 schools in the state, 193 are supposed to be staffed with a cafeteria manager, cook and baker, though schools are occasionally shorthanded. Some schools prepare food for nearby “satellite schools” and drivers deliver those hot meals daily. Temperature checks are done to ensure quality.

Lincoln says Kaimuki High School is a school for two nearby satellite schools, yet is also short staffed. But, he says, passion goes a long way to ensure children have a healthy and warm meal.

“You got to take pride in what you do. My people I have here, they do a good job. I’m not bragging. I was just fortunate to have that,” he says.

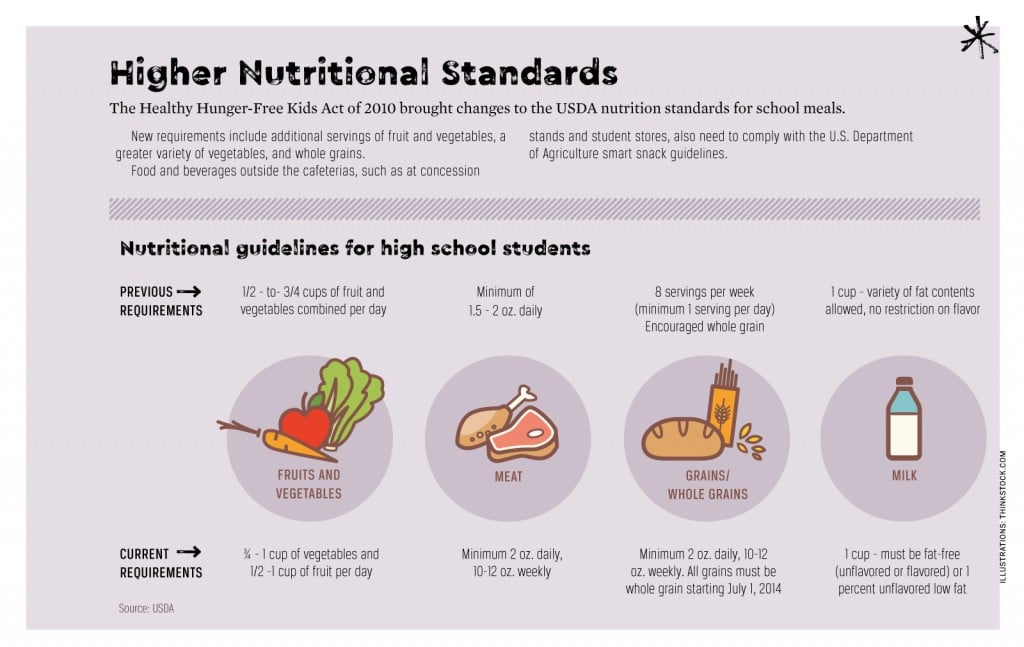

NUTRITION

Lincoln says pizza, kalua pig and nachos are the bestselling lunch items at his school. They might not sound like the healthiest meals, but they are served because salt and fats are limited.

Cafeteria manager Darryl Okamura has served up to 320 meals a day to students at Kaiser High School for the past three years. Okamura, who has been working in the food service industry for 22 years, says flexibility can sometimes be a challenge at the school cafeterias.

“There was more freedom to change the menu in the 1980s. Now the state is more conscious about nutrition value,” he says.

Lincoln says he samples food in the kitchen every day before it’s served to the students to ensure quality.

“I have to, that’s my job. I have to go out there and taste ‘em, check ‘em,” he says.

When students dislike a product, as shown by poor sales, Chambers says, the DOE removes the product. One example: She says chickpeas were eliminated as after-school snacks after poor sales.

A cook at one school, speaking out of earshot of the cafeteria manager, told me that although state guidelines are good, some recipes are hard to follow without ruining the taste. So this cook sometimes alters some aspects of the menu to enhance taste, even if the resulting food exceeds the nutrition guidelines.

“Gotta taste good, or the kids not gonna eat,” the cook says.