2014 Top 250: Changes in the List over 30 Years Reveals Transformation of Hawaii’s Economy

When Hawaii Business published its first Top 250 list 30 years ago, the “Big Five” were still big. The companies that once dominated the local economy were no longer the five biggest companies in the state as ranked by gross sales in 1984, but they were still major players and ranked high on the Top 250: Amfac was No. 1, Castle & Cooke third, Alexander & Baldwin fifth, C. Brewer 10th and Theo H. Davies 14th.

Fast-forward to 2014 and A&B is the only one of the five still on the list. Joining it at the top of this year’s Top 250 are companies that were smaller in 1984 or didn’t even exist back then. Those changes in the list reflect a huge transformation in Hawaii’s economy – changes that mirror national and global trends.

- Healthcare, education and other service industries are now much bigger players in the local economy, and the latest edition of the Top 250 reflects those changes.

- Sugar and pineapple – mainstays of the Big Five – are almost dead, and the most lucrative local crop, seed corn, was not on anyone’s radar in 1984 Hawaii.

- Today, mainland- and foreign-owned companies play a much bigger role in Hawaii’s economy.

- Computerization and other improvements in productivity mean many local companies actually have fewer employees today than in 1984, though they have grown exponentially in revenue.

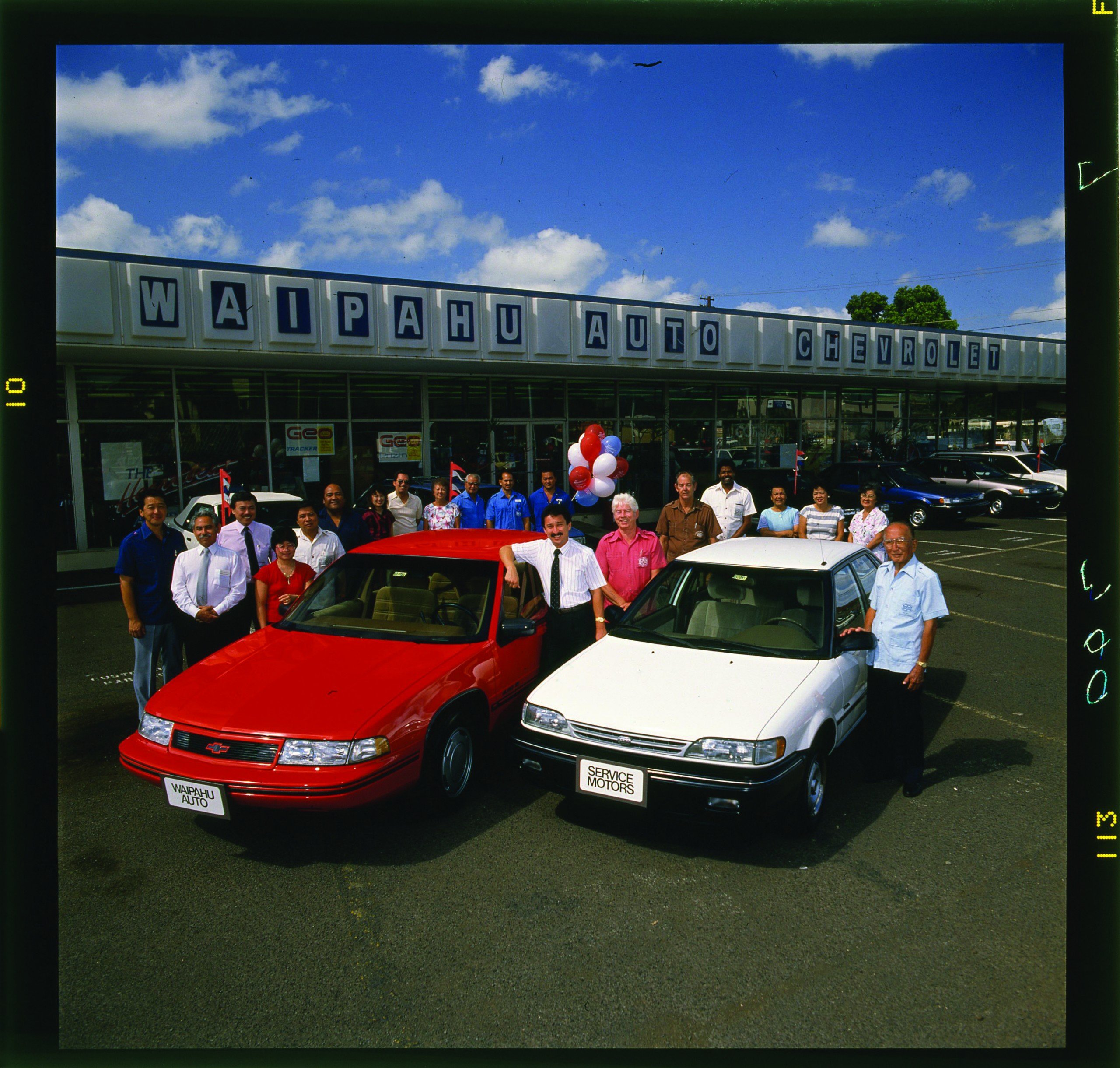

The staff of Servco Pacific’s Waipahu Auto Chevrolet (now known as Servco Auto Waipahu) gathered in 1984 to celebrate Servco’s 75th anniversary.

David Heenan, who was president of Theo H. Davies & Co. in 1984 and is now a trustee for the Estate of James Campbell as it winds down, says the changes have not been good overall for Hawaii.

The demise of the Big Five “had a lot of implications, everything from (reduced) community giving, to a significant fragmentation of the Hawaii business community. You don’t have the handful of organizations I would call heavy-hitters. The corporate gravitas, I don’t think, is the same.”

Walter Dods, arguably Hawaii’s most influential business leader of the past 30 years, says changes in the local economy have created an imbalance.

“The big non-service industries, the big companies that produced income, like the Big Five and Dillingham, have mostly fallen by the wayside and that’s not good for the economics of a society,” says Dods. “Service industries are important, but more important is the industrial base. When you become more and more service-oriented, it’s not healthy for the economy. You don’t want your banks as some of the largest companies, but to serve the large companies.”

Dods saw those changes firsthand: He was CEO and chairman of First Hawaiian Bank, and a chairman or other major player in A&B, Hawaiian Telcom, Matson and other top local companies.

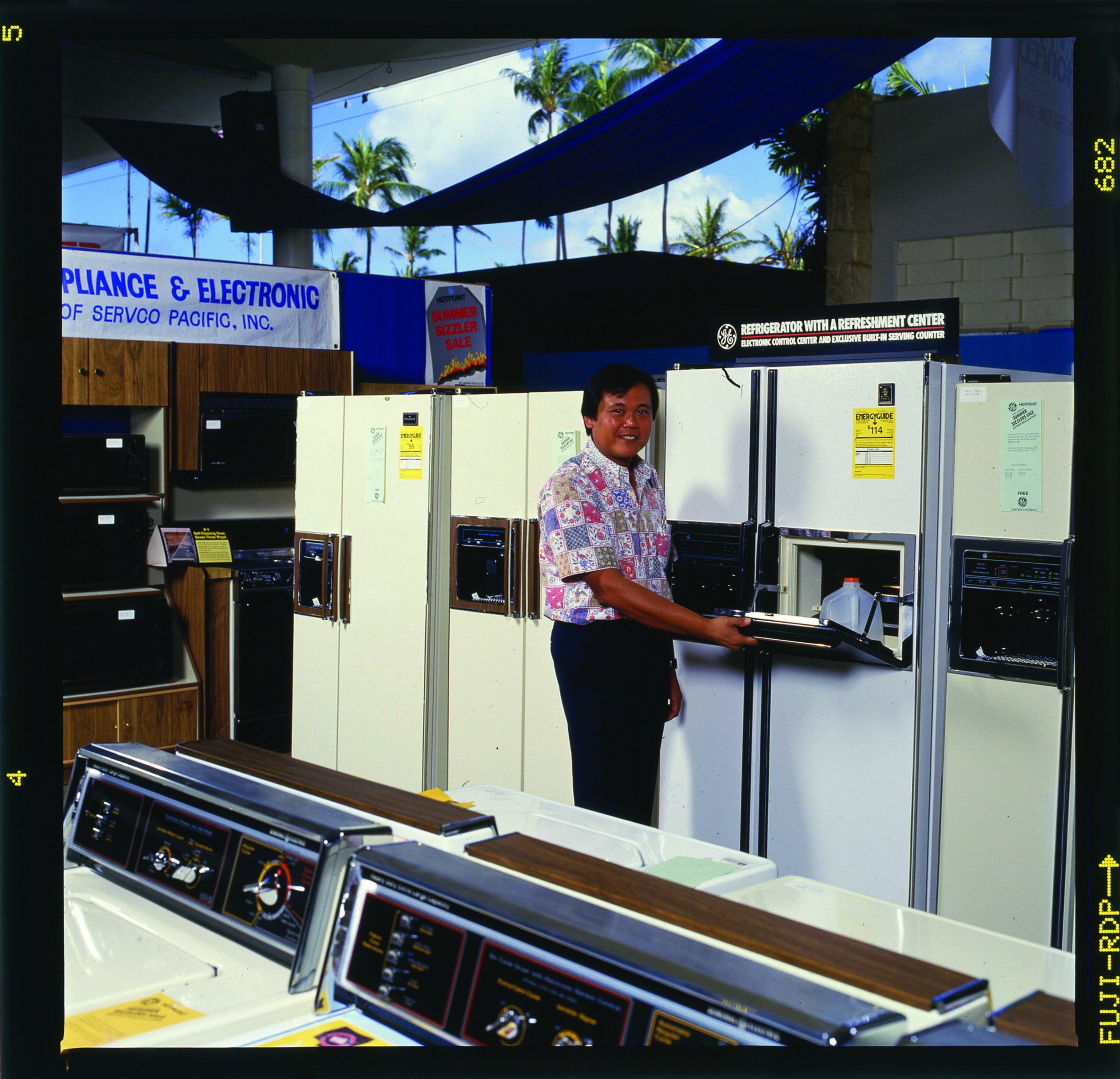

Faustino “Dag” Dagdag shows off the latest GE refrigerator at a Servco display during a 1980s home show at the Blaisdell Center. Photos: Courtesy of Servco Pacific

Heenan also held many key roles in Hawaii’s changing economy: In addition to his positions at Theo H. Davies and the Estate of James Campbell, he was a top administrator at UH. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. He says the changes in Hawaii’s business community reflect national and international trends. For instance, he points to the amalgamation and rebranding of big oil: Exxon and Mobil combined, as did Chevron and Texaco.

“It’s amazing the number of brand names that are no longer on the Fortune 500 or Forbes list, or have been re-branded,” says Heenan. “You’d be amazed at the number of drop-outs, consolidations and re-brands for what seemed to be permanent institutions.”

You don’t have to look far to find similar changes in the Top 250. This year’s No. 1, Hawaiian Electric Industries Inc., owns the electric utilities on Oahu, Maui and Hawaii Island, but now also owns American Savings Bank, which was an independent savings & loan institution in 1984 and ranked 18th on that year’s list. Back then, HEI was fourth on the list.

The growth of healthcare in Hawaii reflects a national trend. HMSA is No. 2 on the Top 250 this year; it was eighth in 1984. The Queen’s Health Systems is ninth now but was 20th back then. Kaiser Permanente is sixth today, but did not submit information for the 1984 list. Hawaii Pacific Health is eighth this year; Straub Clinic & Hospital, now a part of HPH, was 31st in 1984.

The growth of the service sector can be seen in the rise of Servco Pacific Inc., a privately held local company. Three decades ago, it ranked 13th on the Top 250 with sales of $190 million and 1,330 employees – already a big player. It has climbed to seventh this year, with $1.123 billion in gross sales, but, because of greater efficiencies and productivity, it has just 150 more employees than 30 years ago. In the course of those three decades, Servco has become a conglomerate that includes 18 car dealerships, including seven in Australia, and subsidiaries in tire sales, insurance (with an office in Seattle), appliances, and other home and consumer products.

A Reyn’s ad in a 1984 edition of Hawaii Business. Still a Hawaii tradition, 30 years later.

“They’ve been able to transfer their multiple successes overseas, much the way Outrigger has been able to transfer its core competencies to other countries,” Heenan says.

“The two most profound forces that have occurred over the last 30 years, and continue to increase in intensity, are globalization and technology. How well companies adapt to those changes determines who will survive, grow or prosper. Those that haven’t have probably bitten the dust.

“In any business,” Heenan continues, “there are three ways to grow: product, function or geography. Either you add new products or concepts, new functions or new business activities, or expand geographically.

“Every company in Hawaii, particularly a publicly held company, has to grow. Shareholders are looking for growth, so a number of companies have tried to be players geographically. But many found out the hard way that their skill sets weren’t exportable. The Bank of Hawaii, for instance, had a lot of operations in places like Fiji and other small islands, which they’ve recently divested. To their credit, Servco and Outrigger have probably learned from the past mistakes of others, and have become successful multinationals. So it can be done.”

Economist and social scientist Denise Konan says the changes in Hawaii’s economy and society reflect many forces. The change from a plantation, agricultural economy into an economy more dependent on skilled workers also made urban centers grow in importance as rural areas receded. Those changes had much to do with how Congress altered agricultural protections.

Konan, dean of the College of Social Sciences at UH-Manoa, says the decline of the Big Five in Hawaii began as the U.S. phased out protections on sugar, pineapple and other agricultural products to build international trade.

“There used to be strong quotas in place, especially for sugar and pine, but, as they phased those out up through the 1990s through the World Trade Organization, more competitors came on line to serve the U.S. market,” Konan says.

The Philippines and other low-wage countries produced sugar and pineapple more cheaply than Hawaii, so Hawaii’s ag transformed from plantations to smaller farms and more diversified crops.

“The fastest growing of these – seed corn – was not even part of the portfolio in 1984,” notes Konan. Now, the seed corn industry is worth more than Hawaii’s sugar, coffee and pineapple combined, she says.

The change in quotas and other trade barriers also cost Hawaii manufacturing jobs, says Konan.

“For instance, aloha shirts used to be made here and now they’re made overseas. Again, we had quotas in place for American-made clothing and they were phased out … starting around 1994.”

UH economics professor Sumner La Croix says mechanization gradually pushed more and more of the labor force out of the fields.

“If you look at what happened to sugar employment between the 1930s and 1960s, it just evaporated. It went from close to 50,000 jobs down to 14,000,” says La Croix, who has spent the last 15 years on research for a book he hopes to publish next year called, “Hawaii: 800 Years of Political and Economic Change.”

La Croix says globalization has changed what jobs are valued and the skills needed for them. He cites mortgages as an example. “If people don’t like local mortgage quotes, they can talk to someone online and arrange it with a mainland lender.”

Want to invest? “Now people go to e-trade. We’ve seen an internationalization of business.”

During the past 30 years, education has also boomed nationally and in Hawaii. The UH is now fifth on the Top 250

(it did not supply information for the 1984 list).

“The number of jobs in education has almost doubled,” notes Konan. “Tourism is important, but the real growth has been in educational services, in healthcare and professional, technical and administrative jobs. That matches what we see as economies move up a growth pattern. People move out of ag and manufacturing jobs and into more skilled occupations.”

Another trend is the growth of mainland- and foreign-owned companies in Hawaii. Dods says that generally means the best-paying jobs in the local subsidiaries go to people brought to Hawaii by the offshore owners and that’s especially true in Hawaii’s biggest industry, tourism.

“The visitor industry is mostly not owned locally. The Hiltons, Hyatts and Marriotts are not owned here, so you don’t have the higher paying jobs here in Hawaii.”

On top of that, jobs in tourism and other service industries generally pay less than jobs in an industrial economy, where you pay a lot of engineers, Dods says. “In a service economy there are a lot more fast-food type jobs.” That’s why, he says, more households have both husband and wife working than in the past, because they need the money to survive.

The government and military have remained strong sectors of Hawaii’s economy over the decades, despite recent spending cuts. Heenan says Hawaii’s strategic location in the Pacific means it should continue to play an important role in national defense. But he worries about the weakness of Hawaii’s technology and scientific sectors.

What will the next 30 years look like? What will be the dynamic new companies on Hawaii’s Top 250 list in 2044?

Dods says Hawaii needs to expand into niche sectors. “Tourism, the military and the government are the big spenders. We need to find three to five smaller legs because we won’t find a fourth, larger leg. … So hopefully our niche markets will be astronomy, aquaculture, some energy – at least for our own Islands’ self-sufficiency – and maybe some small, pocket areas of innovation. We really don’t have the great research institutions – the Harvards, Stanfords and MITs – to make it easier for innovation industries to flourish around them. So it’s harder for us. But we’ll find niche industries to excel in. That’s what I see as our future.”

La Croix believes we’ve already started to add strong legs to the stool.

“I think we have a nascent high-tech industry, though it’s a difficult place to support high-tech. If it grows, it will be because of skilled labor, proper infrastructure or proper tax support. I think we’ve made some strides in our educational reforms in the public schools and UH is making all sorts of adjustments to reach a higher graduation rate and ensure that graduates have a better set of job skills.

“When I look at infrastructure, for a long time we’ve lagged behind in broadband, but we also seem to be addressing that better. And, in 2013, we passed a research and development tax credit. … Frankly, this is one of the best moves the state has made with tax policy in recent years.”

Konan agrees innovation is key to the next 30 years. “We can take our expertise globally in all kinds of areas, especially to Asia … We’re moving into more innovation and that gives me a lot of hope.”