$14 Billion to Fix Hawaii

The tab has finally come due.

For decades, Hawaii neglected its critical public infrastructure. Inadequate roads and highways have left us with mind-numbing traffic jams, not just in Honolulu, but in Kona, Kihei and Lihue. Our harbors – the entry point for food, fuel and other necessities – lack enough piers and yard space. Thirty-eight percent of the state’s bridges are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. More than 120 million gallons a day of raw sewage passes through sewers that are bursting at the seams. And our children attend schools and colleges with crumbling buildings and leaky roofs. The roster of major repairs and capital-improvement projects is almost endless.

But at least now we have some idea what it’s all going to cost. A report released this month by the Hawaii Institute for Public Affairs says the state and counties will spend at least $14.3 billion on critical infrastructure over the next six years. This includes more than $2.6 billion for water and the environment, the bulk of it to repair Oahu’s aging sewer system. Another $7.8 billion will have to be spent on transportation, including harbors, airports, highways and transit. More than $3 billion of that is destined for the rail project alone. Another $3.7 billion will go to public facilities, especially major renovations at public schools and new construction at the University of Hawaii.

If these figures seem too abstract, consider a single infrastructure investment: the Waimalu Sewer Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Project. Waimalu has always been a graveyard for sewers: The original system, installed in the 1950s, lasted barely 30 years. The replacement system broke down in even less time. The marshy ground next to Pearl Harbor can’t support heavy, concrete sewer pipes, so long runs tend to sag and crack. Old-timers in the neighborhood say that sediment gathers in these low spots, and the city has to send sucker trucks once a week or so to clear them. And when it rains hard, the sewers back up and flood the streets.

In 2008, the city signed a contract with the Frank Coluccio Construction Co. to replace the neighborhood’s system with new sewers that can survive in the mushy ground. The price tag of the two-year project: $45 million.

Multiply the cost and effort of the Waimalu project by the hundreds of other infrastructure projects around the state, and you get a sense of what $14.3 billion will get us.

Even these figures may grossly underestimate the cost of the infrastructure problems facing the state, says Russ Saito, state comptroller and director of the Department of Accounting and General Services. That’s because the numbers that agencies provided for the HIPA report are likely skewed toward projects that have already received funding.

“It depends on how the questions were asked of the departments and what assumptions the departments used in providing information,” Saito says. “For example, I assigned my public works administrator to provide that information. But he wasn’t comfortable giving them numbers that were not already appropriated. So he limited his dollars to the amounts that have been appropriated.” In short, infrastructure needs that haven’t yet been appropriated may not show up in the HIPA report. A true assessment of the state’s infrastructure may identify billions of dollars in additional needs.

Hawaii’s infrastructure problems are hardly unique. In its 2009 Infrastructure Report Card, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation a “D.” The society said the nation faces a collective $2.2 trillion shortfall in infrastructure spending just over the next five years. Broadly speaking, the gap reflects similar needs in Hawaii.

Honolulu County is paying $45 million to replace the sewers in Waimalu (that includes $7 million in federal stimulus funds). Honolulu’s overall spending on sewers this year totals $345 million. | Photo: David Croxford

Local Spending

That’s not to say nothing’s being done here. The last few years have seen a nearly unprecedented investment in infrastructure by both the state and counties. Saito cites the Department of Education as an example. “When they started looking at it back in 2001,” he says, “they said they had a backlog of about $700 million. Now, they’ve got it down to about half that – $350 million or so.” These deficits, he points out, are the price tag for neglecting to properly maintain the schools to begin with. “If you had been spending what you should have been spending on repairs and maintenance on an ongoing basis, you wouldn’t create this backlog.”

The Lingle Administration hasn’t restricted its infrastructure spending to schools. According to DAGS, more than $3 billion is currently appropriated to state agencies for capital improvements, $1.9 billion of which is for contracts that have either already started, have been awarded, or are currently open for bid. The lion’s share – more than $2 billion – goes to the Department of Transportation, which makes its infrastructure spending a fascinating study.

The state has initiated, for example, an ambitious $842 million Harbors Modernization Plan, which will address the shortage of space and adequate yard facilities in all major Hawaii ports. The dozens of critical improvements include:

• A new deep-water pier and a 70-acre container yard at Honolulu Harbor’s Kapalama Military Reservation;

• A new pier and a third harbor plus some dredging in Hilo;

• New piers and liquid bulk storage at Kauai’s Kawaihae Harbor.

Funding comes from increases in harbor user fees and revenue bonds, and the impetus comes largely from the Harbor Users Group, a collection of shipping companies, emergency response groups, the petroleum industry and other groups most affected by the decaying harbors. But, like the 12-year, $2.3 billion Airport Modernization Plan (see story, page 55), much of the funding must still be appropriated and released in future years. So these projects are far from guaranteed.

The fate of the Lingle Administration’s most important infrastructure initiative, the six-year, $4 billion Highways Modernization Plan, is in an even more precarious limbo. This ambitious plan, which includes funding for 183 separate projects across the state, was passed by the Senate; but, lacking support in the House, was deferred by the conference committee. The bill will likely be advanced again in the next session, but in the interim, the Department of Transportation will have to make do with its regular appropriation (plus a one-time shot of nearly $500 million in stimulus money).

Brennon Morioka, director of the Department of Transportation, is quick to acknowledge the challenges facing the Highways Administration. “I think we’re sorely backlogged,” he says. “Not just in the amount of new infrastructure to be provided, but also in the level of maintenance of what we currently have. So, we’re fighting two battles. One is to use what funds we have to meet the continually growing demands of the public and industry. But there’s also the battle of making sure we’re properly maintaining them so we don’t just build them and then let them fall apart.”

The dollar figures provide some details. “We’re probably about $150 million to $180 million behind in maintenance backlog,” he says. To put that in context, he points out, the state typically spends $60 million to $70 million a year on maintenance. Making up this maintenance deficit will obviously take many years. “And based on the HMP estimate,” he says, “once we catch up, we still have to spend $80 million or $85 million a year on maintenance.” In other words, the highways maintenance budget will have to increase about $10 million a year just to keep up with normal wear and tear.

“And that’s just maintenance,” Morioka says. New construction and major repairs are an even more daunting problem. “Looking out 20 years,” he says, “there’s about a $7 billion infrastructure gap.”

Federal Funds

One advantage for highways is the availability of federal funds, including Hawaii’s annual allotment from the Federal Highways Trust Fund, which is typically a grant of about $140 million a year. Although this money cannot be used for normal maintenance and operations, Morioka points out, these federal funds account for about 80 percent of capital spending.

Of course, the state also benefits from the maneuvers of our congressional delegation. Mazie Hirono, for example, as the first Hawaii representative on the House Transportation Committee, is able to help local officials identify specific funding opportunities. And, of course, as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Sen. Daniel Inouye is the source of hundreds of millions of dollars a year in earmarks, much of which makes its way to transportation projects like Saddle Road on the Big Island.

Last year, DOT also benefited from the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, receiving a one-time payment of $126 billion. (The Great Recession may provoke one of the largest periods of infrastructure investment since the Great Depression.) Morioka notes that this money was the source of some controversy in Washington. “We were criticized from the federal level about why we were so slow to spend the money,” he says. But he defends the department’s approach: “I think we actually did a better job than most other states in choosing the right kind of projects that really address some of our infrastructure backlogs.” The work has been diverse: bridge replacements in Windward Oahu, a new bike path on Kauai, a new road in Kona. “A lot of other states just did resurfacing,” Morioka says. “To us, that was shortsighted. Something like resurfacing a road employs people for like three months, whereas our projects are going to employ them for three years. I think we utilized our funds very effectively.”

The average daily, two-way commute between Kapolei and urban Honolulu takes 140 minutes, the state Department of Transportation says. The annual personal cost for each commuter is an average of $61 a minute, according to a state estimate. | Photo Courtesy: Department of Transportation

Revenue Bonds

Despite this outside money, DOT is still dependent on local fees to meet its infrastructure goals. Its budget is almost evenly divided between capital-improvement projects, and maintenance and operations, each of which receives $200 million to $250 million a year. “So, in the big picture of the overall highways program,” Morioka says, “federal funds account for only about 34 percent of the budget. The rest comes from the state highway fund.” This fund, separate from the state’s general fund, is financed by a variety of user fees.

More important, it also covers the highways division’s considerable interest payments on its revenue bonds, which pay for the transportation projects. Morioka notes, “Our highways modernization proposal increased the gasoline tax, increased registration fees, increased the weight tax and increased the rental vehicle surcharge. Together, these would have increased the annual revenues into our highway fund so we could pay for the annual debt service on a $2 billion bond float.” That $2 billion, added to DOT’s $1.5 billion budget and the $500 million in stimulus funds, accounts for the $4 billion budget Highways Modernization Plan.

Without those increases in fees, Morioka acknowledges that DOT has probably swallowed as much as it can chew. “We’re almost at our limit in terms of what our current revenue streams can afford,” he says. “The administration has really pushed the limits in terms of spending down available balances without jeopardizing our bond ratings.” In fact, according to the state’s 2008 comprehensive annual financial report, the highway fund coverage – the ratio of its available revenue to the amount required to cover its existing debt obligations – is already at 103 percent, very close to the statutory single-year limit of 100 percent. So, until the department is able to raise fees, widespread improvements of the state’s transportation infrastructure will continue to wait.

The moribund Highway Modernization Program included more than $57 million for rehabilitating H1’s Pearl City and Waimalu viaduct. | Photo Courtesy: The Department of Transportation

City Lights

Compared to the state, Honolulu county is even more dependent on revenue bonds to pay for its ambitious sewer modernization plans. That’s because, unlike transportation, wastewater infrastructure can’t rely on a steady diet of federal funds. It’s true that the city, like the state, did receive some federal stimulus money (more than $7 million went into the Waimalu Sewer Project). But the county’s Department of Environmental Services relies almost exclusively on sewer fees, both for maintenance and operations, and for its massive plan for capital improvements.

The need to fund those capital improvements was highlighted, of course, by the disastrous Ala Wai sewage spill in March 2006. “But even prior to that,” Mayor Mufi Hannemann says, “our administration said that we were going to incrementally raise sewer fees. Sewer fees had not been raised for the last 10 years or so. Also, those funds were always being diverted to do other things. So I made two pledges: One committed to this long-term plan of raising sewer fees; and, since 2005, they’ve gone up by 275 percent. The second was that we would never raid the sewer fund again; whatever we raised would go back to sewer purchase only.”

As with the state, these increases in revenues have allowed the Department of Environmental Services to float the revenue bonds necessary to seriously address the sewer system’s most egregious shortcomings. Many of these, like sanitary sewer overflows and faulty pumps at the major treatment plants, were the subject of existing consent decrees with the Environmental Protection Agency. Nevertheless, the current administration has shown real enthusiasm for fixing the problems. “This department has been meticulously fixing the collection system and making upgrades to our pumping stations and our wastewater treatment plants,” Hannemann says, “to the tune of $1.5 billion. And we’ve committed to another $1.6 billion for the next six years. That’s a lot of money.” Indeed, much like the DOT, the department is approaching the legal limit in terms of its allowable debt load – in this case, 18.5 percent of its revenues.

Tim Steinberger, director of environmental services, puts the city’s efforts into perspective. “Just to give you an idea,” he says, “$80 million used to be a good year for CIP. Now, $250 million to $300 million is kind of the norm. This year, we’re doing $345 million.” Most of that money, he points out, has gone into the most critical elements, like the Waikiki bypass and the contracts to replace the great trunk lines, such as those running along Ala Moana and Kalanianaole Highway. “We’ve addressed most of the big pipes now,” he says. “And when I say ‘big pipes,’ I’m talking about 30-inch to 42-inch nodes. Now, we’re looking mostly at pipes in the 15-inch to 24-inch category.” Perhaps more importantly, he says, some of the projects on the books are starting to address the eight-inch pipes. “And about 78 percent of our island is 8-inch diameter pipe.”

But there’s a catch. Since 1995, the EPA consent decree has largely shaped the city’s investment in wastewater infrastructure. Last year, EPA added to the city’s troubles by revoking a longstanding waiver on the requirement to use secondary treatment on wastewater prior to releasing it into the ocean. At issue is whether the city should be required to build these secondary treatment facilities at its Sand Island and Honouliuli plants, a requirement the city says will likely cost more than $1 billion.

Although the Hannemann administration has vigorously contested the science behind this ruling, EPA has so far stuck to its position. Currently, the two are in intense, quasi-secret negotiations over details. How those negotiations turn out may decide whether the city finishes its work on the wastewater collection system, or builds the treatment plants. Privately, city officials acknowledge that installing secondary treatment is probably inevitable. For his part, Hannemann says he has always advocated for a “global settlement” – basically, a long enough timetable for the city to afford both. For now, however, the future of the city’s single largest infrastructure system remains up in the air.

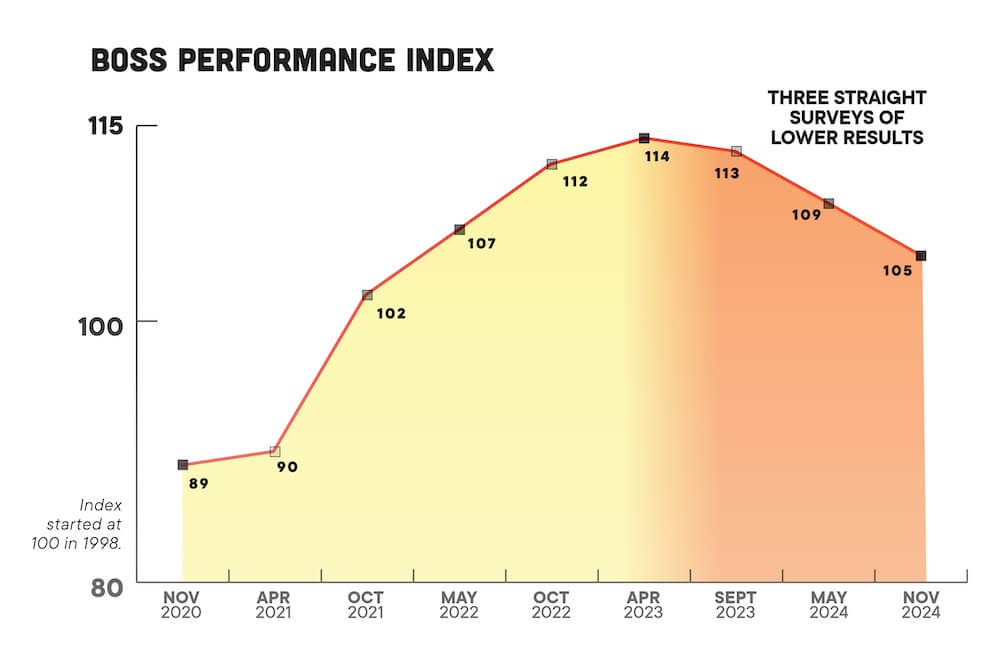

BOSS survey

Grim Year for Construction Companies, Survey Indicates

Almost all Hawaii construction companies were hit hard in the past year and expect flat or lower revenues again this year, according to the BOSS survey conducted by Hawaii Business and QMark Research.

In a telephone survey conducted in April, 403 top executives were interviewed from a mix of large, medium and small companies doing business in Hawaii. Of those interviewed, 109, or 29 percent, identified themselves as being involved directly or indirectly in construction.

The executives were asked to describe their revenue, pre-tax profits and staff changes in the past year.

The chart below compares responses from all those surveyed to the responses of construction executives. In every category, construction companies fared worse.

The chart on the following page shows the expectation of construction executives for the coming year.

| INCREASE | STAY THE SAME | DECREASE | ||||

| Overall | Constr. | Overall | Constr. | Overall | Constr. | |

| Gross revenue | 18% | 16% | 14% | 7% | 64% | 76% |

| Profit before taxes | 20% | 19% | 16% | 14% | 55% | 62% |

| Employment changes | 10% | 6% | 51% | 40% | 38% | 54% |

Expected Revenue This Year for Construction Companies

| Substantially more than last year | 12% |

| About the same as last year | 50% |

| Substantially less than last year | 39% |