Tutu’s Tale [Sponsored]

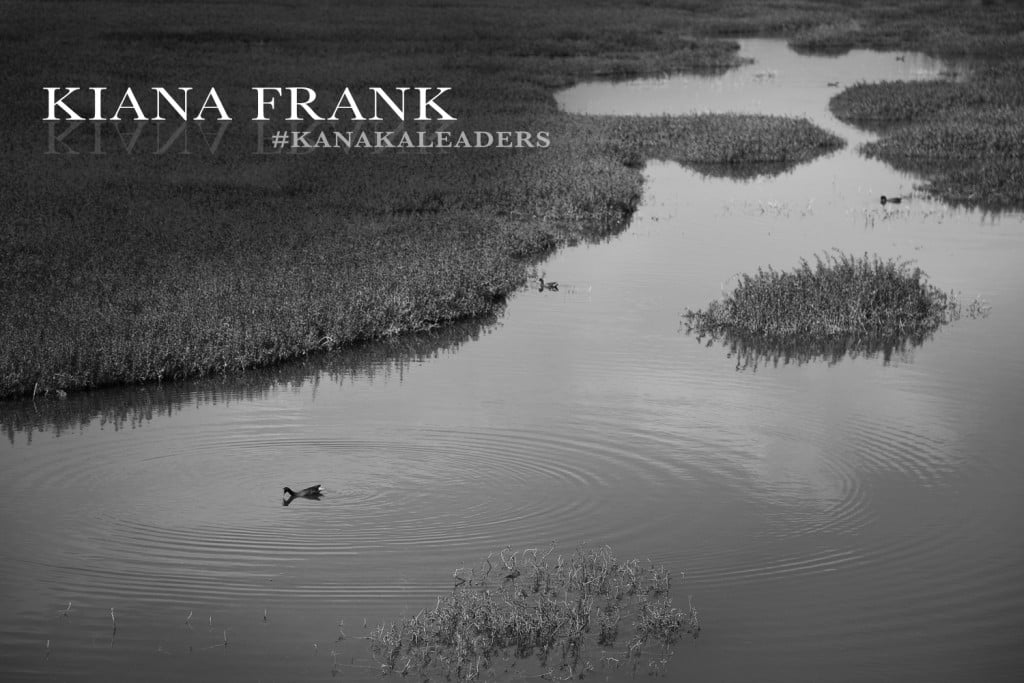

Kiana Frank is one of those people that knew her career path from childhood. As a keiki from Kailua, Oahu, she was a self-described “inquisitive, young explorer,” discovering the natural nuances of Kawainui Marsh. Her grandmother told Kiana the story of Kawainui’s lepo ai ia or edible mud that was said to be delicious and nourished Kamehameha the Great’s warriors after the Battle of Nuuanu. Hearing this Hawaiian history, Kiana took a shovel and notebook to Kawainui and conducted many experiments to find the lepo ai. Her findings at the time concluded that the mud was not delicious.

When she got older she noticed an old painting of Kawainui at her grandmother’s house that depicted the marsh as an open, unencumbered fishpond. This depiction was a stark contrast to the Kawainui that Kiana grew up in and it shocked and amazed her at the same time. Realizations and discoveries like the aforementioned would abound as she continued her education, graduating from Kamehameha Schools Kapalama in 2004; University of Rochester with a B.S in Molecular Genetics in 2008; Harvard University with M.A. Molecular Cell Biology in 2010 and Ph. D. Molecular Cell Biology in 2013. Currently, she is an assistant professor at Pacific Biosciences Research Center, Kewalo Marine Laboratory with the University of Hawaii Manoa. You can hear her passion for science in her answers to the interview below, and if you read in between the lines you will also hear the voice of her kupuna as well.

Hawaii Business magazine: What are your professional responsibilities at Kewalo Marine Laboratory?

Kiana Frank: My primary duty as a scientist is to contribute to the progress and advancement of scientific knowledge. As such – my job is to ask questions, to seek answers, and to share stories built on observation and experimentation. I study microorganisms in our ahupuaa ecosystems and the role they play in shaping the functionality of that aina –microbes to meaai. I believe that my kuleana as a kanaka research scientist is to perpetuate place-based knowledge and ecological-based studies that foster values and concepts of traditional management by integrating with contemporary technology and scientific knowledge systems. My kuleana as a kanaka professor is to provide my haumana with knowledge and practical skills, encourage their intellectual curiosity, engender connections between their work and their community, and fully engage them in the process of science.

How long have you been working in the field of science?

I would argue Iʻve been working in science my entire life. I was born a scientist. The process of science – observation and experimentation – is how I connect with my place and my culture and I fostered that scientific inquiry as a young child playing in the mud of Kawainui marsh. But, I guess, I truly began my research career in 2001 as a freshmen at the Kamehameha Schools and I have been actively engaged in scientific research ever since.

Who was the biggest inspiration in your career from a Hawaiian cultural perspective and how did they influence you?

Paepae O Heeia has been the biggest most influential inspiration in my career. Working with this organization, on this particular piece of land, has completely transformed me and helped me to more deeply connect to my roots, paepae ke kahua, and reflect on and refine my identity as a kanaka, as a scientist and as a kanaka scientist. They have taught me to sit still, see and kilo; they have trained me how to lift even the most daunting of pohaku; they have fitted my lips with the sounds, words, phrases and moolelo of my ancestors; and they have grounded me in aina learning techniques. I learn from and am inspired by the incredible back breaking hard work, day in and day out that they do to restore, not just a fishpond, but our community. I am honored to have received incredible ike and manao from each and every individual on the staff over the years and am humbled by their outpouring of aloha towards me. I would not be where I am today, who I am today, without the support and kokua of this organization.

What do you think is the kanaka maoli advantage in science?

What do you think is the kanaka maoli advantage in science?

Being a kanaka maoli scientist informs the way I observe, question, respond, think, believe, feel, act, and learn. Greg Cajete, a Tewa author and Native American studies professor, describes it so eloquently: “Native science goes beyond objective measurement honoring the primacy of direct experience, interconnectedness, relationship, holism, quality and values, and they are specific to tribe, context and cultural tradition.” Kanaka oiwi scientists bring so much more to this industry than our contemporaries because we stand on the shoulders of our ancestors, building off generations of assimilated ecological knowledge, strengthening our hypothesis, refining our experimental designs and enabling more holistic conclusions. That spiritual/ancestral layer that is absent in majority of Western Science practices connects us more deeply to our place of study, fosters deeper understandings, perpetuates pono practices, cultivates stronger relationships and enables us to communicate our work with the community more effectively.

What is your kuleana and how are you embracing it?

I believe that it is my kuleana to help elevate the level of Native Hawaiian Science and transform the perception of science in our communities. I believe that science is an important tool in our community, not only to drive data-based policy, but to advance our understanding of our place and how we fit into that place. We need to engender indigenous scientists that have deep connections to their place and the kuleana to protect them. This not only builds our representation in STEM fields, but also builds capacity to put skilled Hawaiians “at the table,” grants us more independence as a people and enables our ability to implement novel sustainable practices that align with our values. We must reclaim our identity as scientists. Our culture and our practices are based off of kilo and the scientific method. Science is not this foreign western construct, it’s what we’ve always done, its apart of who we are. We need our communities to recognize that science is not separate from our culture and our identity but rather, science is a strength of our indigenous culture.

To auamo this kuleana means more than just being an awesome well published scientist who happens to also be kanaka maoli (the University’s perspective of success) – it means transforming how we do science and innovating how we share and communicate science of today and of the past. I am humbled by this kuleana, and approach it with feet firmly planted in the aina, eyes looking to the past, a spirit guided by my kupuna, a heart full of aloha, hands willing to hana and a mind imi i ke kumu. I am immersed in a values-driven interdisciplinary research program that integrates biology, geochemistry, and ike kupuna to address globally relevant questions that are directly applicable within our backyards. My research helps to understand the connectivity from microbe to meaai to promote the restoration and sustainability of Hawaii’s agricultural and coastal marine resources. I use contemporary techniques to interpret scientific observations encoded in our moolelo to help show connections between our stories and the meanings behind it. I identify as a storyteller. I weave stories with science to explain the world around me from micro to macro scales – advancing our understanding of how we fit into and influence our place. It is my kuleana to share these stories with my community and the world. My current passion project is innovating the way we share and teach science – through context specific, place-based, culturally grounded, values based dance expressions – connecting science back to aina and engaging haumana, ohana and lahui in fun, accessible and relatable science education.

Where would you like to see yourself professionally in 10 years?

I’m hoping that over the next 10 years I can help to transform the culture of science at the University – helping us to move towards a more authentic indigenous place of learning (rather than a school for indigenous people). I would like to push for an indigenous science curriculum that acknowledges Hawaiian knowledge and methodology as equivalent to the Western practices. I want to help promote and kokua pipelines for faculty cultural competency training to educate non-local faculty on the history and pono practices of our places. I want to do amazing science that contributes significantly to the advancement of science in a way that honors the mana and ike kupuna of our aina. I hope to achieve a tenured position and continue to hooulu haumana through the STEM educational auwai, showing them that STEM is one of our most powerful tools on our voyage to achieve sustainability. I hope that in 10 years I will see some of these students as colleagues, and we will have exponentially grown the number of kanaka in STEM faculty positions. I hope that in 10 years we will have seen transformations in how “science” is perceived in Hawaiian communities. I hope that in 10 years we begin to recognize that science is one of the biggest strengths of our indigenous culture and that we must reclaim it to innovate the practices of our future.

What do you want the future of Hawaiian leadership to look like tomorrow?

Oiwi leaders need to be the pivotal intersection points across fields/people/place – to show how different industry, organization, place, values, missions etc. connect to build a scaffold that is much bigger than the sum of the parts. We need those leaders who continue to inspire me everyday – those warriors that take action and lead by example. Those who jump-in, get dirty, do what needs to get done because “choice no choice.” We need leaders who are willing to make waves, to innovate our thinking, to transform how we do things to build bridges and hooulu lahui.