Rapid Ohia Death – Threat to Hawaii’s Water

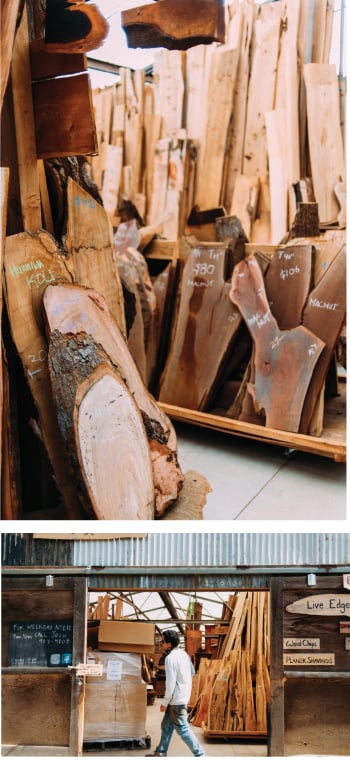

The low-slung warehouse sits on the edge of a small industrial park just outside Waimea.

Behind it are the humped, green foothills of Kohala, the oldest of the Big Island’s five volcanoes, and low, heavy clouds inch down the mountain like a vaporous glacier. A wood plank hung on the side of the tin warehouse reads “Kamuela Hardwoods.” The company, owned by Alex Woodbury and Joshua Greenspan, has been in business since 2010, reclaiming urban trees that have been felled for one reason or another and selling the wood to builders, furniture makers and other craftspeople in Hawaii and beyond.

Its warehouse is a trove of timber, each wood’s common name scrawled on it in chalk: koa, pheasant, lychee, cypress, Cook pine, rainbow gum eucalyptus, “sexy sugi,” Hawaiian kou. But there’s one species you won’t find in Kamuela’s warehouse: ohia lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), one of Hawaii’s most important and populous native trees. Despite its availability, Woodbury hasn’t accepted any ohia wood for the past three years. He’s afraid of it. Or rather, he’s afraid of what it might carry.

Since 2010, a previously unknown strain of a fungal pathogen known as Ceratocystis fimbriata has been killing Hawaii Island’s ohia. The disease, known as rapid ohia death, has spread to at least 47,000 acres of Hawaii Island, from Lower Puna to Honuaula, north of Kona. On average, it kills 20 to 25 percent of an area’s trees per year, and it kills fast. Once infected, an ohia can succumb within weeks, strangled by the fungus, which colonizes a tree’s sapwood, cutting off the flow of water from its roots.

To date, there have been no confirmed cases in Waimea, Kohala or along the Hamakua Coast – or on any other islands – and Woodbury wants to keep it that way. “The last thing we want to do as business owners here is contribute in any way to the spread of any sort of disease,” says Woodbury from his warehouse on Lalamilo Farm Road. “The coqui frog coming out of Kona was a perfect lesson. You don’t want to be on the front end of releasing a plague.”

Since the mysterious fungus was discovered in 2014, its effects have been felt by business owners, artists, cultural practitioners, government officials and dozens, if not hundreds, of scientists, many of whom have relocated to Hawaii to help combat the devastation. Simply put, rapid ohia death, often abbreviated to ROD, is one of the most significant environmental crises Hawaii has seen in recent history.

“It has the potential to terminally alter Hawaiian ecosystems, water resources and cultural practices,” says David Benitez, an ecologist at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, where 14 cases have been confirmed. “ROD is a threat to our quality of life.”

GROUND ZERO

Josh Greenspan, arborist and co-owner of Kamuela Hardwoods, walks through his shop near Waimea filled with specialty wood harvested on Hawaii Island. His business no longer works with ohia wood because of the fear of spreading rapid ohia death. Photography by Megan Spelman

In Lower Puna, the epicenter of the outbreak, much of the ohia forest is dead or dying. The silvery trees are barren, stark against the lush, green understory, like a pine forest several years after a wildfire. Like most diseases, rapid ohia death began with just a few isolated cases. In 2010, homeowners began calling the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (CTAHR) and complaining that their trees were dying. Foresters investigated but didn’t find anything unusual. They assumed it was one of the dozens of diseases known to affect ohia.

But the volume of calls increased. By 2012, as lab tests came back negative for known diseases, this was obviously something experts had never seen before. “There were hypotheses being thrown around: maybe it’s geothermal, maybe it’s related to vog. But nothing else was dying,” says Corie Yanger, an education and outreach specialist with CTAHR and its first staff member working exclusively on ROD.

By the time plant pathologists discovered the presence of Ceratocystis fimbriata (different strains have plagued kalo and sweet potato, but never before ohia) it was mid-2014, and the disease was spreading like wildfire. With at least a basic understanding of how trees were being infected, the state quickly sought to prevent the disease from leaving the island. In August 2015, the Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) quarantined all ohia products. Anyone wanting to ship ohia – whether wood, leaves, flowers or even seeds – now was required to have their cargo inspected.

“That’s a tough thing to do, to put restrictions on that kind of commerce,”says Flint Hughes, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service.

HDOA, he says, is “putting the emphasis where it needs to be, and doing so at some risk of criticism.”

Hughes was even more impressed by the local business community. “The president of Young Brothers immediately understood what was at stake,” he says. “(Glenn Hong) said, ‘We don’t need to wait for anybody. We’re imposing a ban ourselves.’” More than a month before the quarantine went into effect, Young Brothers notified customers that it would require, effective immediately, that “all shipments containing ohia logs or ohia products be accompanied by an HDOA certification of inspection, similar to the certificate required for live plant shipments.”

Roy Catalani, Young Brothers’ VP of strategic initiatives and external affairs, says the company’s leadership learned about ROD from a meeting of the Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species. “Even with the level of evidence at the time, it was clear that rapid ohia death was a major threat,” he says. “And it was also somewhat clear that, although it wouldn’t be convenient, there was a means to test and verify whether or not certain products posed a risk to other islands.”

RESTRICTIONS FOLLOWED

Though there are exceptions, most business owners on Hawaii Island say they support the quarantine and are happy to comply with the new guidelines, which require those shipping ohia to obtain an HDOA PQ7 permit and a certificate of inspection for each shipment. But the new rules have taken their toll. Woodbury, who no longer accepts ohia but had an inventory of close to 8,000 board feet when the quarantine went into effect, says the time it took to supply the wood samples, wait for the lab results and get the certificate of inspection ate into his bottom line, not to mention additional losses if any portion of his inventory was found to be contaminated (it wasn’t).

“It took two months to get a load of material out that I would have otherwise sent out in a week,” says Woodbury, who sports a graying mustache and a thin stripe of a goatee and looks built for rugby, even in board shorts and mud-stained rubber boots. “And it cost me a couple of hundred bucks for the sampling. So there’s a monetary impact, for sure.”

Jeff Anderson, who owns and operates a sawmill in Ocean View, hasn’t been so lucky. Ohia poles – milled from unwanted trees and used as support beams for everything from homes to hotels – make up much of his business. Several of his logs tested positive. Of the 500 or so shipments he’s made in the past year, he says, only about a dozen ohia poles have tested positive for ceratocystis, yet demand has waned, especially on Neighbor Islands. He estimates that he sold about half the usual amount of ohia poles this past year. “I know I could do a lot more business off island,” he says.

Others are less affected by the new rules. Companies like Big Island Wood Products, which sells ohia mainly as flooring, don’t have to bother with lab tests because the wood has been kiln dried. (The USDA has determined that the fungus is inviable if the wood reaches temperatures in excess of 130 degrees Fahrenheit or has a moisture content of less than 20 percent.)

Top left and bottom right:

Pieces of ohia are cut through to show ravages of the disease. The two other pictures show ohia flowers. Ohia wood photography by Megan Spelman. Ohia flower photos: Thinkstock.com

Some say the restrictions aren’t tight enough. Woodbury, whose business partner is a certified arborist, says he would like to see HDOA restrict the transport of ohia on the Big Island. A quarantine may prevent the spread of rapid ohia death to the rest of the archipelago, but what about Hawaii Island? “I mean, this isn’t a zombie apocalypse movie,” he says.

He worries that tree companies and green-waste facilities are unwittingly infecting healthy forests. It’s possible. ROD’s distribution largely has followed the pattern of the winds, moving southwest with the northeasterly trades. The fungus itself isn’t windborne, but dead ohia are highly attractive to ambrosia beetles – another non-native species – which bore into the wood, creating an ultra-fine sawdust called frass as they go. That frass, which in an infected tree may contain Ceratocystis, can travel miles if airborne. If humans saw into the wood, they can create the same effect.

Which is why Woodbury refuses to mill ohia, even though it’s legal. He and his partners use every part of the trees they get, selling the slash as wood chips and donating sawdust. “If we did that with ohia, we’d spread (ROD) all over the island almost instantaneously,” he says. “We’re absolutely not willing to take that chance.”

Several sources who were part of the quarantine discussions say on-island restrictions were discussed. But HDOA determined that to quarantine parts of Hawaii Island would have been unenforceable. Instead, it would rely on education and outreach to discourage on-island transport. But Woodbury says the honor system won’t work. He sees ohia poles “moving all over the place, all the time. I would be shocked if we aren’t unknowingly spreading rapid ohia death all over the island.”

WHAT A TREE IS WORTH

UH Manoa forestry researcher J.B. Friday leads fellow scientists through a forest in the Puna district of Hawaii Island where rapid ohia death has devastated many of the trees. Photo by Megan Spelman

Compared to a tree like koa (Acacia koa), ohia lehua is a small part of Hawaii’s forest industry, which itself is dwarfed by industries such as tourism and agriculture. Ohia’s real economic value – to say nothing of its cultural importance – is as a keystone species of Hawaii’s forests. The state has 1 million acres of ohia forest across its islands, which account for nearly a quarter of Hawaii’s total land mass. Ohia is the state’s most common native tree and native forests are between 50 and 80 percent ohia.

Healthy forests are crucial to the overall health of any ecosystem, contributing to healthy air quality, the recharge of groundwater and wildlife habitat. But, in Hawaii, their importance is amplified by the Islands’ unique evolutionary history. “Hawaii is a tiny, isolated land mass, and, as a result of that, you have evolutionary processes that are unparalleled,” says David Benitez, the national park ecologist. “Consequently, you have an extraordinary concentration of rare and threatened and endangered species found nowhere else on Earth.”

As a keystone species, ohia helps support a bevy of native plants and animals. It is the first tree species to colonize a lava field, eventually transforming an uninhabitable landscape into a dense and thriving forest, creating along the way volcanic soils and habitat for native birds, such as the apapane (Himatione sanguinea).

Yet it’s surprisingly difficult to put a monetary value on the ohia trees. Kimberly Burnett, a research economist at the UH Economic Research Organization, says the effects of an invasive species like the coffee berry borer are easier to measure because coffee has a price. “Although there is a small market for ohia timber and ohia honey, that’s not the primary reason we care about it,” Burnett says. The tree’s most significant value is, perhaps, cultural. “It’s in so many Hawaiian chants, it’s a part of Hawaiian dance and music – to try to quantify that impact is not necessarily useful,” Burnett says. “To replace the lei in Merrie Monarch with another flower and look at the difference in price – that’s one way to do it, but it’s something that’s not really replaceable.”

To actually calculate the economic value of a healthy ohia forest, one has to understand the forest’s relationship to Hawaii’s water. “Water has an economic value that we can measure and quantify and monetize more directly,” Burnett says.

No other tree in Hawaii’s native forests “captures water the way ohia does,” says CTAHR’s Corie Yanger. Look at an ohia – at its branch architecture, its densely clustered leaves, at the lichens and mosses that often colonize its bark. “All of that creates a sort of sponge for the water that falls,” she says. “That water filters through the forest and then seeps into the ground, and that recharges our aquifers.” Strawberry guava, one of the main species moving in as the ohia die, is smooth-barked and shallow-rooted. It has almost the opposite effect during rainfall, increasing runoff, which could raise the risk of flooding and brown-water events along Hawaii’s coast.

Its disruption of the island’s natural hydrology may be ROD’s greatest economic impact.

“Just thinking about the impact to our freshwater supply, our irrigation water for agricultural lands, that is billions and billions and billions of dollars,” Yanger says.

An exact figure is hard to calculate, but a 2008 study estimated that the groundwater recharge of the Pearl Harbor Aquifer on Oahu was worth somewhere between $4.5 billion and $8.5 billion. The question is how ROD will affect groundwater recharge. Researchers aren’t sure, but a 2011 investigation by the U.S. Geological Survey found that invasive species – plants like strawberry guava – reduced estimated groundwater recharge by 85 million gallons per day. If water costs roughly $4 per thousand gallons, that’s a $340,000 loss every day.

Of course, there are other economic impacts, such as the future effect on tourism. According to a report released in April of this year, more than 1.8 million people visited Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in 2015 and spent roughly $151 million on Hawaii Island. If the park’s ohia trees were devastated on the scale of Lower Puna, and even 1 percent of those visitors chose to travel elsewhere, it would mean a loss of $1.5 million a year. And that’s just the park.

Homeowners are worried about their property values, but it’s less clear whether the real estate market will be substantially affected. It’s easy to imagine that being located within a once-thriving but now dead forest would seriously hurt home prices, but Burnett isn’t so sure. Although people personally value ohia, she says, “I’m not sure that it’s something where it’s inherently going to change the value of that property.”

Clark Allred, the owner of Big Island Wood Products, a flooring manufacturer, agrees. A few years ago, he was on some land in South Kona during an appraisal. The property was predominantly ohia, with a few koa mixed in, and he watched as the appraiser valued the ohia at zero.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing,’ ”

Allred says. “Even though it’s a beautiful wood and it’s got all this cultural significance, it still has no financial value.”

“The most disheartening thing I ever watched,” he continues, “was 120 acres of beautiful old-growth ohia being bulldozed so coffee could be planted.”

Allred worries ROD will hurt the tree’s value. Already, he says, the wood has a stigma. “It’s tainted somehow,” he says. “It’s got people looking to other (woods).” Jeff Anderson feels it, too. He continues to ship ohia poles around the island, which requires neither a permit nor a certificate of inspection.

“I feel like a moonshiner with my ass hanging out driving through town,” he says.

But Burnett says any stigma is likely temporary. The cultural value of a tree that plays such a powerful role in Hawaiian legend won’t be permanently marred by the current crisis, she says. In fact, she says, residents are shunning the wood because they respect it. It is a sacrifice made out of a desire to protect their island, their forests, their ohia.

Hawaii’s scientific community is working furiously to better understand and hopefully halt the advance of Ceratocystis fimbriata, setting up information tables at community events and circulating a list of guidelines for anyone working with infected trees. Researchers recommend cleaning equipment, shoes, and clothing with rubbing alcohol and washing vehicles with soap. For local business owners, it’s largely a game of wait and see. Some are going about business as usual, just with a few more delays and a little more paperwork. Others aren’t willing to take that chance. Most are awaiting a verdict about whether a heat treatment might work. There is talk of using a method similar to kiln drying that might render infected wood safe to transport, but there’s been no official recommendation from the USDA.

Woodbury, for one, hopes an answer comes soon. With the number of trees dying every week, there is no shortage of ohia timber. “If we can’t figure out a way to safely utilize it, it’s all gonna go to waste,” he says. Until the science is sound, however, Woodbury won’t be milling ohia. “If there’s a moratorium on taking it off island without testing it, we’re probably better off just not cutting it.”