Doing Business Island Style, 2014 Remix

The world has changed. Is Hawaii still stuck in the past? Or were we ahead of the times all along?

Remember 2004?

That year, a BlackBerry was the height of executive cool, while the first iPhone was still three years away. Facebook was being coded in a Harvard dorm room, and MySpace ruled the emerging world of social media. George W. Bush was running for re-election, and Barack Obama started the year as an obscure Illinois state senator, largely unknown even in the state where he was born. The world has changed a lot since 2004.

That was the year Hawaii Business published “Local Style for Lo-Los,” our initial look at what’s distinctive about doing business in Hawaii. We described a business style founded on Hawaiian values and influenced by Asian (particularly Japanese) sensibilities. We wrote about small businesses that would let regular customers pay later if they’d forgotten their wallets. And we had some advice: “Build relationships, then do deals.” “Check your ego at the airport.” “No talk stink.”

In 2004, we were still smarting from the parting shot of Evan Dobelle, former president of the UH system, who managed to commit all three of those no-nos when he hightailed it back East under a cloud of overspending allegations and then sourly wrote in the “Chronicle of Higher Education” that Hawaii needed to “come off the plantation.”

Ouch. “Are the Islands a land of aloha,” we wondered, “or a hopeless backwater?” Would the “high-speed, needed-it-yesterday world leave tradition-bound Hawaii behind?”

A lot has changed in 10 years. Have we?

“Nope,” says Richard Brislin, a professor emeritus at UH Manoa’s Shidler College of Business Administration, who loomed large in our 2004 article.

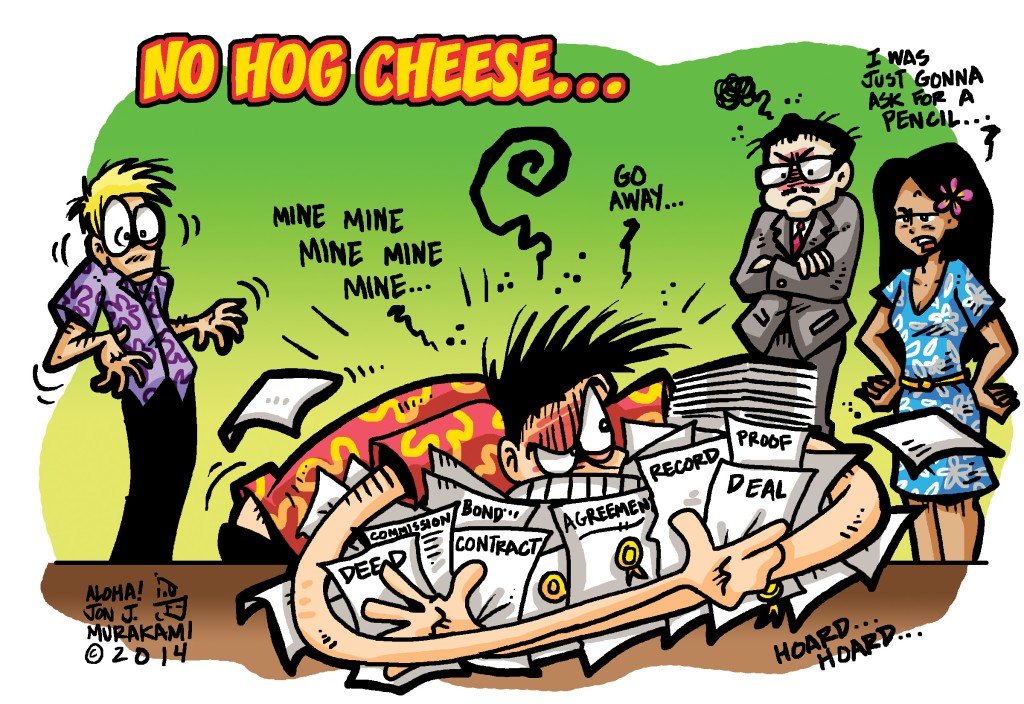

Mike McCartney seems to agree. The president and CEO of the Hawaii Tourism Authority sums up Hawaii’s business culture in 2014 this way: “No talk stink. No make big body. And no hog cheese.” For non-pidgin-speakers, that’s, “Don’t badmouth people; don’t act entitled and arrogant; and don’t take more than your share without giving back more than you get.”

One business owner, who asked not to be named, said she’d recently heard a well-meaning, Hawaii-loving mainlander describe the state’s way of doing business to a potential international client as “Aslowha.”

In Hawaii, when we meet you, we still ask what high school you went to. We still bring food to meetings, although the food itself is more likely to be Paleo friendly or gluten free. And we still want to know who you are before we do business with you.

Island State of Mind

Why haven’t we evolved? Because the conditions that created our business style haven’t changed. Hawaii is an island state, more than 2,300 miles away from any other habitable landmass. Greater Honolulu may be classified as a mid-size American city, but no other U.S. metropolis is surrounded on all sides, for thousands of miles, by far more fish than people.

That means there’s no “next-best” option for relocation. Tired of Los Angeles? Get on the freeway and in a few hours you can be in San Diego or Las Vegas. If you move from New York to Boston, you can still see your Big Apple buddies on the weekends: it’s two hours by train. Seattle has Portland; San Francisco has San Jose and Berkeley.

In Hawaii, you can’t get in your car and drive far in any direction, so we keep running into each other: at Longs, at Zippy’s, at Costco. And whereas in other parts of the world there might be six degrees of separation between people, “in Hawaii, it’s more like two,” says Alex Kagawa, a budget analyst at the state Department of Education.

IQ360 principal Lori Teranishi recalls a trip to Longs on the day after she’d unloaded the Matson container that had carried her belongings from the San Francisco Bay area back home to Honolulu: “I had no makeup on. I just looked terrible. It was 7 in the morning. And even though I had been away for 24 years, I saw three people I knew.”

Yet we love it here. Hawaii residents came in dead last, tied with Montana and Maine, in a 2014 Gallup poll that asked people across the country, irrespective of actual plans, whether they wanted to move out of their state. In most of the contiguous 48, an itinerant life and starting over someplace new are still romanticized.

What happens when you live on an island that’s irreplaceable to you? It means that what local dealmaker Jeffrey Watanabe said in 2004 is still true. “You better not make messes,” he said back then. “I’m sure in a big city like New York or Chicago you can do that and move on. But not in Hawaii.” There’s no place to move to.

“What are big metropolitan cities built on?” asks Mark Noguchi, chef and co-founder of community food group Pili Hawaii, “They’re built on commerce. And they’re built on big business. To survive there, you have to have what I call metropolitan mindset. Lead, follow or get the (bleep) out of the way. Here in Hawaii, it’s a little bit different,” he says, because very few people are here just for their careers.

Don’t Burn Bridges

Glenn Furuya, president and CEO of the business consulting group Leadership Works, describes two styles of doing business: “circular” and “linear.” A circular, Asian- and Polynesian-style culture is “collaborative and interdependent.” A linear, Western culture is “focused, assertive, independent.” A critic of Hawaii’s more circular methods might say that a linear culture gets you somewhere, whereas a circular culture lands you right back where you began. But in interviews for this article, it’s another circular metaphor that dominates the description of the way we do business: What goes around, comes around.

Living in an island community “does moderate our behavior,” says Teranishi. “It does keep us honest more than in other places. You’re not going to behave in certain ways if you know it’s going to come back to bite you.” On the mainland, she continues, “There’s more anonymity, just because there are so many more people – a feeling that, ‘Well, I can burn this bridge because there will be another one.’ Here, you burn one bridge and it stays with you for a long time.”

Is our business community really nicer? Yes, says Noguchi – at least in public. “You hear it all the time: ‘I can’t stand the way you do business here in Hawaii. You have to be nice to everybody.’ That’s Hawaii, you know, and they knock it, but that’s how it is.”

Go Slow to Go Fast

In our June issue’s feature on leadership, Hawaii Business quoted Hawaiian Electric Industries CEO Connie Lau as saying that people and companies in Hawaii most often don’t have a single bottom line: “In Hawaii, we talk much more about double or triple or even quadruple bottom lines. … We’re not so strongly financially oriented; we also care about quality of life, balance of life and preserving what’s special about Hawaii.”

Having multiple criteria for success means a more complicated business equation than just financial profit and loss. When you and the person on the other side of the boardroom table share an island and a community, when you’ll run into each other at Longs, when you both intend to stick around, your questions become longer range: Is this good for Hawaii? By doing this, am I strengthening my place in the community or weakening it? How is what we’re doing going to affect others?

Ben Godsey, president of ProService Hawaii, has a term for this long-range business approach, borrowed from psychology: Hawaii has a “relational culture.” A more transient, dispersed population focuses on short-term deals with a clear-cut outcome, because social and other reverberations won’t be felt; the person you’re doing business with may disappear next year and, in the interim, you’re not as likely to run into them in any other context. A “transactional culture,” says Godsey, asks, ‘I’m doing this for you; what are you doing for me?’ Here, it’s a relational culture. Over a long period of time, what are the relationships you’re building?”

Furuya agrees: “In Hawaii, relationships come first, transaction comes second. Go slow to go fast.”

Missouri-born Amanda Corby, principal of the public relations and outreach firm Under My Umbrella, learned that the hard way: “I was of the mindset, ‘OK, we’re going to sit down and get to business.’ But sometimes there needed to be a lunch just to get to know each other, with no business (discussed) whatsoever,” says Corby. “It took so much longer to build that trust. But once you have that trust, then you can start talking business.”

Trust takes time to build, says Godsey, who worked in big metropolitan areas on both coasts before moving to Hawaii. “For the first few years (in Hawaii), I’d say it was an obstacle.” But Godsey, who was raised in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, “recognized there was a similarity to where I grew up, where long-term relationships mattered, and reputation mattered.” He had to prove that he had skin in the game and honorable intentions, and part of that was patience. “I just kind of watched and talked to people. At some point, people start to take you under their wing and share with you more.”

Business 360

A relational business culture that considers the whole person may be hard to break into, but it has significant upsides, Godsey says. One of them is the expectation that even the most successful professional will live a multifaceted life. “I believe it’s much easier to have balance here than it is in most places,” he says. “In the Bay Area, in NYC, from what I experienced, the time you’re expected to spend away from your family is quite a lot.” Here, he says, there’s the expectation that “you’re going to do your work in the day, and then you’re going to spend time with people in the community, working on nonprofits, working in the schools – and that’s refilling your spirit. It’s not just, ‘Hey, I get to go home earlier and spend more time with my wife and kids.’ It’s that I have other ways to add value besides doing strictly my job.”

Teranishi says that our broader social definition of success matters to work-life balance: “If you’re an executive, and you’re in an environment where you’re judged only by how much money you make, it’s easy to think only of that. But I don’t think people here look at executives who don’t have a family life, or don’t contribute to the community (but who make a lot of money) as successes.”

The financial incentive to step away from the office and contribute in other ways is significant, Godsey says, because people will choose to hire you if they encounter you in a wider range of situations across a longer span of time. “What I really like about Honolulu, and Hawaii, is that it’s what you do with a larger body of work that matters. It’s not just this one thing. There’s a real value in the consistency over time, and the body of work that you put in, both at work as well as in the community. That’s what allows people to make choices about whether they want to do business with you and your firm.”

Teranishi concurs that having an active community life is a big contributor to business success in Hawaii. “People genuinely want to know who they’re doing business with here,” she says. “Family connections, community and school connections, friendship connections, all of those things factor into the equation when people make assessments on who to do business with.”

Being known by your business community in multiple contexts also makes it harder to have a business facade, says Corby. “It’s almost more real, doing business here. People are their real selves,” she says. “On the mainland, you might be one person by day and a completely different person at night. I feel like here, you’re yourself in your business and in your personal life, and there’s less separation between the two.”

Human Resources

Island life is partly about living with options that aren’t inexhaustible. Meli James, president of the Hawaii Venture Capital Association, says that on the mainland, decisions are made based on the assumption of a bottomless pool of capable human capital. “They’re either in, or they’re out. And then (if they’re out), there’s always someone else that can fill in.”

The lack of a safety net can be useful for sharpening skills, says Noguchi. “A mentor told me, ‘You want to find out how good you are? Go cook with the guys on the East Coast, because they don’t give a shit (about you as a person).’ The motivated ‘I’ll-work-for-free-18-hours-a-day’ cook, they’re a dime a dozen there.” In a transient environment, it’s up your game or go home, because there is always people just like you, waiting to take your place.

But business in Hawaii “is about the people who are here,” says James. “You’re working with this limited resource.” James is also program manager for the startup accelerator Blue Startups, and she tells the story of the first cohort of applicants for the three-month mentorship program: “We had hundreds of applicants. All these Hawaii teams, applying or interviewing. And of course we only accepted eight teams, out of the hundreds.”

That meant that there were a lot of “really interesting, talented entrepreneurs” who didn’t make the cut, but her thinking was: “Maybe that idea wasn’t going to be the one, but something else would.” Fresh from the Bay Area, James says she expected to see the most promising teams apply again right away with a different idea, but that’s not how it turned out. “People on the mainland are way more aggressive,” she says. “I kind of assumed everyone was going to apply every time, but I just didn’t see them again.”

She had to try a different tack: “I had to take it upon myself to reach out and make a phone call, talk to them, invite them, keep the conversation going so it’s fostering a community – so that people feel like they’re a part of the community and they want to keep coming back. It’s not just, ‘You suck, don’t ever apply again.’ We don’t have enough people here to do that.”

Teranishi, of IQ360, has a different way of putting it. Doing business in Hawaii “may take us longer, but we do it in a way that doesn’t make people feel compromised, or less than.”

Access and Accountability

It’s not only your clients and business partners you run into everywhere. The state’s small size means that you’ll also cross paths routinely with, say, the governor. “There’s much more proximity to people in positions of power. If you look at the top 25 CEOs, you see them all the time in their boroboro clothes. You see them without makeup,” jokes Teranishi. “And I think it’s weird that I see Governor Abercrombie so often. When I was living in California, I never saw the senators. I see ours at Zippy’s.”

It makes for a less stratified society, she continues; it’s hard to be an “all high-makamaka person, tromping on the little people,” when they are going to catch you making your 6 a.m. run to get coffee.

Lawmakers are not only unusually visible, but unusually accessible, adds Virginia Pressler, executive VP for Hawaii Pacific Health. “In most (other) places, I hear, ‘Oh, I can’t get in to see my legislator.’ In Hawaii, they’re open door.”

Abercrombie says that when you’re accessible, it also “increases accountability, because things generally move from the abstract into the three dimensional.” HTA’s McCartney gives a real-world example: “If I give a (business) referral and it doesn’t quite work out, I can expect a call from my friend: ‘Wow, I thought you said this place was good, but not good.’ Now I feel an obligation, and I’ve got to go fix it.”

“In Hawaii,” Corby says, “if you do not operate with integrity, it will bite you in the ass. This is too small of an island.”

The New Economy

McCartney has another thought about Hawaii’s

way of doing business, where relationships rule, the boundaries between business and personal life are fuzzy and you can’t escape your reputation: “The original social-media model, is us.” He adds, “Business in this town is done through trust.” Brislin agrees: “trust is core” to the way Hawaii does business. James also calls Hawaii a “trust economy.”

Rachel Botsman, a former director of the William J. Clinton Foundation and author of “What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption,” also believes that “the currency of the new economy is trust,” but she’s not talking about Hawaii. In her book, Botsman describes how the recession, the rise of social media and 24/7 smartphone use have led to a national and global “trust economy” – a digital landscape in which “reputation capital” is priceless.

On the Internet, your actions live forever. They can establish a pattern of good behavior or mark you as someone to avoid. As people establish online presences over a long period of time, that accumulated capital can be gold, say “trust aggregator” companies like TrustCloud, featured in Forbes and The Wall Street Journal, which generate a “portable trust score” that functions as an online reputation. TrustCloud’s website explains, for example, that your behavior on the travel review site TripAdvisor “can indicate you’re a well-traveled and helpful person,” while your behavior on Facebook “can indicate you’re connected, transparent and social.” In 2012, Wired declared, “Welcome to the reputation economy.”

Miles Spencer, the Connecticut-based chairman of TrustCloud, says, “It used to be that our neighborhood was our community, and a handshake would allow you to borrow a lawnmower or send over a babysitter. What’s happened in the last 10 to 20 years is that the Internet has become our neighborhood.” Spencer adds, “Maybe it was Don Draper and the marketing Mad Men who got it into our heads that corporate brands were things we could trust, rather than each other.”

Trust. Reputation. Relationship. Reciprocity. Gordon Gekko, Hollywood’s icon of late 20th-century capitalism, famously said, “Greed is good,” and he might rather die before he let any of those other words cross his lips. But, in a world where products are increasingly difficult to differentiate from each other, even multinationals like The Coca Cola Co. are touting the importance of giving back to a larger community as the most reliable way to ensure brand loyalty.

Discussing Coca Cola’s global sustainability priorities (“women, water and well-being”), the company’s global director of human and cultural insights, wrote in Britain’s Guardian newspaper, “Pursue societal benefits and profits will ensue.” Government institutions have also come around: Canadian Mark Carney, current governor of the Bank of England, recently said, “Prosperity requires not just investment in economic capital, but investment in social capital.” You could make an argument that one of the major business mantras of the second decade of the 21st century is “No hog cheese.”

What does it mean to do business, Island style? At its best, it means factoring sustainability into every decision – not just of environment, but of community and relationships. It means not being able to escape the consequences of your actions, and having multiple bottom lines. It means knowing that if you make a mess, you need to clean it up.

What’s changed in the last 10 years? Not us.