Government and Civic Engagement in Hawai‘i Need to Change

Part 2: How to Increase Hawai‘i’s Low Voter Turnout

There’s no silver bullet: Action is likely needed on several fronts to get more people to the polls though skeptics say some efforts may have little or no effect.

By Noelle Fujii

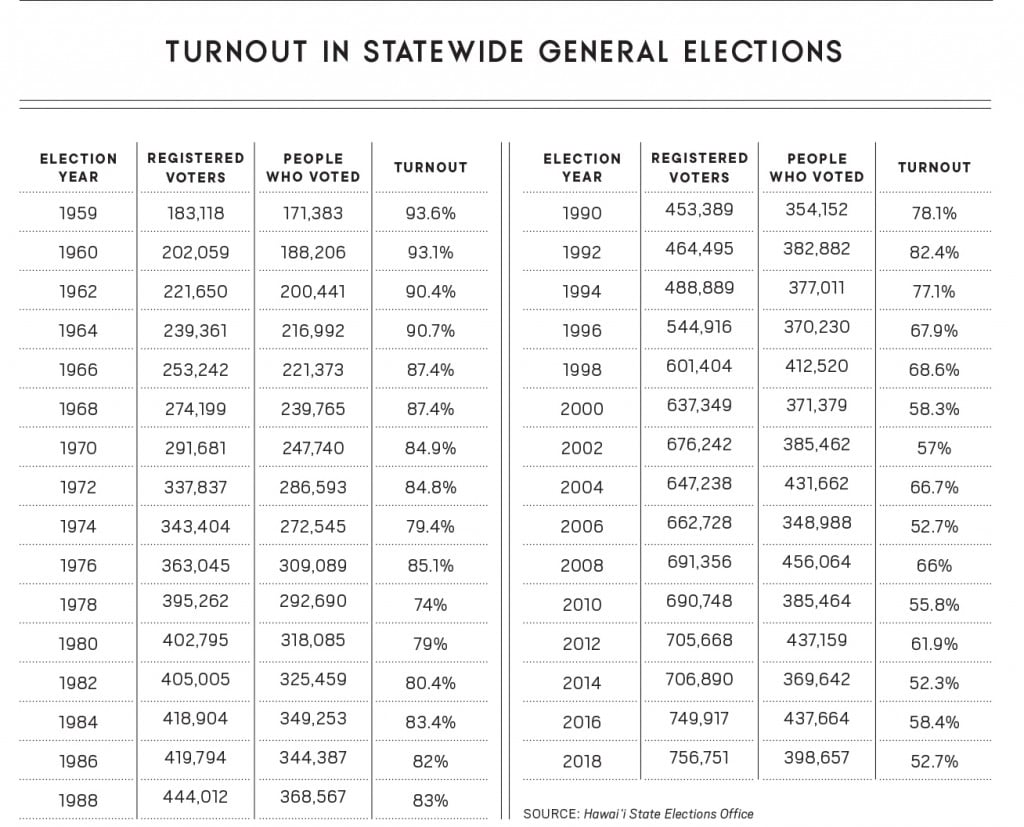

Hawai‘i is well-known for its low voter turnout. Only 52.7% of registered voters cast ballots in the 2018 general election. If you combine the population of adults who are registered to vote with those who are eligible to vote but don’t register, the turnout is much lower: 44%.

“Any way you look at it, Hawai‘i has one of the lowest turnouts in the country,” says Colin Moore, political analyst, associate professor of political science and director of UH Mānoa’s Public Policy Center. “There’s no dispute about that.”

It wasn’t always this way. About 93% of registered voters voted in the 1959 and 1960 general elections. The state’s transformation from a high to a low turnout state is “the great mystery of Hawai‘i politics,” Moore says, but there are several theories as to why. He says one theory goes like this: Hawai‘i politics is dominated by the Democratic Party – more so today than at any time in the past – and being essentially a one-party state means elections are less competitive, which leads some people to think their votes won’t matter. Another theory is that with all of the things clamoring for people’s attention, they just might not be interested or have the time to become informed on the issues and candidates.

He says the low voter turnout is a symptom of general disengagement from politics and civic activities in the Islands. It’s concerning, he says, because it can start a vicious cycle that leads to less voter turnout and less engagement.

Dylan Armstrong, former vice chair of the Democratic Party of Hawai‘i’s O‘ahu County Committee and a member of the Mānoa Neighborhood Board, says Hawai‘i’s low turnout is a symptom of the state’s economic problems, such as a high rate of homelessness and lack of affordable and available housing. People facing these problems have so much else to worry about that they can’t focus on voting.

Voting allows citizens to weigh in on some of the big issues that Hawai‘i faces, and low voter participation can impact how the Islands deal with its biggest challenges, says Janet Mason, co-chair of the League of Women Voters of Hawaii’s legislative committee: “Voting is the way we’re going to perfect a better Hawai‘i, continue to make it a good place to live. And sometimes I don’t think people quite connect the dots.”

People interviewed for this story say there’s no one solution to improving Hawai‘i’s low voter turnout. Instead, it’ll take a little bit of everything: big system reforms that make voting and registering simpler and more convenient for busy citizens, plus more civic education and engagement with different demographics.

3 DIFFERENT WAYS TO MEASURE VOTER TURNOUT

OUT OF TOTAL REGISTERED VOTERS:

This is how the state Office of Elections determines voter turnout. By this measure, Hawai‘i’s 2018 general election voter turnout was 52.7%.

OUT OF CITIZENS ELIGIBLE TO REGISTER AND VOTE:

By this measure, Hawai‘i’s 2018 voter turnout was 44%. This is how the Census Bureau measures turnout.

OUT OF THE POPULATION OF PEOPLE AGED 18 AND OLDER:

This includes all of the voting-age population, including people who are ineligible to vote, like noncitizens, felons and people who are mentally incapacitated. This total does not include people in the military or civilians living overseas. By this measure, Hawai‘i’s 2018 voter turnout was 39.3%.

Big System Reforms

The state Legislature this year passed a measure that would enact all-mail voting across the state, starting with the 2020 primary and general elections. At press time, the bill was awaiting the governor’s approval. The governor has until July 9 to sign the bill into law, veto it or let is become law without his signature.

Oregon, Washington and Colorado conduct all elections entirely by mail, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Currently, Hawai‘i only allows all-mail voting for special federal, state and county elections usually held when a politician dies or retires in midterm. However, a pilot program had previously been authorized for all-mail voting in Kaua‘i County in 2020.

In recent elections, more people have voted via absentee ballot than in person, according to the state Office of Elections. Scott Nago, chief elections officer, says because so many people vote via absentee ballot, it’s almost like Hawai‘i has two voting systems. Switching to statewide all-mail voting, he says, will mean returning to a single system and save an estimated $750,000 per election cycle – by eliminating the cost of Election Day officials who staff and support polling places.

Proponents of all-mail voting say the change will make voting simpler and more convenient for Hawai‘i’s busy working population. Voters would have several weeks to mail in their ballots or drop them off at designated locations.

“With vote by mail, things are even easier for people,” says Brodie Lockard, a board member of Common Cause Hawaii. “They don’t have to fill out a form to receive an absentee ballot – the thing is automated – and every tiny obstacle that we can remove for people to vote gets a few more people to vote.”

“With vote by mail, things are even easier for people,” says Brodie Lockard, a board member of Common Cause Hawaii. “They don’t have to fill out a form to receive an absentee ballot – the thing is automated – and every tiny obstacle that we can remove for people to vote gets a few more people to vote.”

Willis Moore, a professor of U.S. history at Chaminade and a member of the Downtown-Chinatown Neighborhood Board, is among those people who are skeptical that voting by mail will increase Hawai‘i’s turnout, especially because people can already vote by absentee ballot.

Brett Kulbis, chairman of the Honolulu County Republican Party, thinks people will miss the civic experience of voting in person alongside their neighbors. He says he’s also concerned about voter fraud, where a person can vote for another voter or tell that voter who to vote for. Colin Moore, the political analyst, says voter fraud in the U.S. is rare and unlikely to be decisive.

Several other voting reform measures passed at the Legislature this year: a Senate concurrent resolution requesting that the Legislative Reference Bureau establish a task force to review Hawai‘i’s voter education system, a bill that requires mandatory recounts of any close votes, and a bill that calls on the attorney general to prepare a layperson’s translation of proposed constitutional amendments in English and Hawaiian.

Other legislative measures died, including bills that would implement ranked choice voting, automatic voter registration and a process to automatically preregister or register public and public charter school students who are 16 and older. Ranked choice voting is when voters rank the candidates by preference and if no candidate receives a majority of first-place votes, multiple rounds of tabulations follow, with the lowest vote-getter in each round being eliminated. Proponents think it – as well as automatic voter registration – would encourage more people to vote. Ranked choice voting is already used entirely or in part in Australia, New Zealand and Ireland, as well as Maine, and such cities as San Francisco, Minneapolis and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Corie Tanida is the former executive director of Common Cause Hawaii and now a consultant with the Center for Secure and Modern Elections. Although she advocated for automatic voter registration, she says systemic voting reforms won’t guarantee higher turnouts. “I’m sure if there was a silver bullet, we would have run with that, lawmakers would have done that,” she says. “Vote by mail, automatic voter registration, online (registration), these are just … modernizing, streamlining, and these are the low-hanging fruit. It’s the systemic changes that we can have a hand in.”

Reaching NonVoters

Experts say that young adults, minorities and poorer people generally vote in lower numbers than older, white and more affluent people. Reaching them will take more than just big system reforms.

Only 24% of Hawai‘i’s 18- to 24-year-old citizens voted in the 2018 general election, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By comparison, 57% of citizens aged 65 and older voted.

Ian Ross, Makiki district chair for the Democratic Party of Hawai‘i, says the lack of young voters creates a cycle of disengagement and means the issues young people care about will be discussed less or not at all.

“I think that’s the fundamental problem we have to wrestle with and why I suggest this all across-the-board, throw-everything-at-it type of solution because this is a dire problem in Hawai‘i,” says Ross, a Millennial and member of the Makiki/Lower Punchbowl/Tantalus Neighborhood Board.

He adds that Hawai‘i needs to do a better job of civically engaging people. O‘ahu neighborhood board elections, he says, which are conducted online in odd numbered years, also have low turnout – in 2019, only 18,000 people cast ballots islandwide. “The neighborhood board meetings are actually one of the most important types of institutional strengths I think Hawai‘i has to build on,” he says. “If we are to see Hawai‘i return to some of the highest voting rates in the country, a part of it is going to be because neighborhood boards were able to connect with more people.” (Honolulu County is the only county with neighborhood boards.)

Focus on Teenagers

Several organizations work to increase voter turnout among young adults. Lockard says Common Cause Hawaii has focused on encouraging youth civic participation by lecturing at high schools and colleges, and last year piloted a civic ambassador program at UH Mānoa and Kapi‘olani Community College in partnership with nonprofit Kanu Hawaii. Student ambassadors visited classes to talk about the importance of voting and registered over 300 new voters. He says Common Cause hopes to continue the program for future elections. The state Elections Office also conducts a young voter preregistration program to encourage students as young as 16 to preregister to vote.

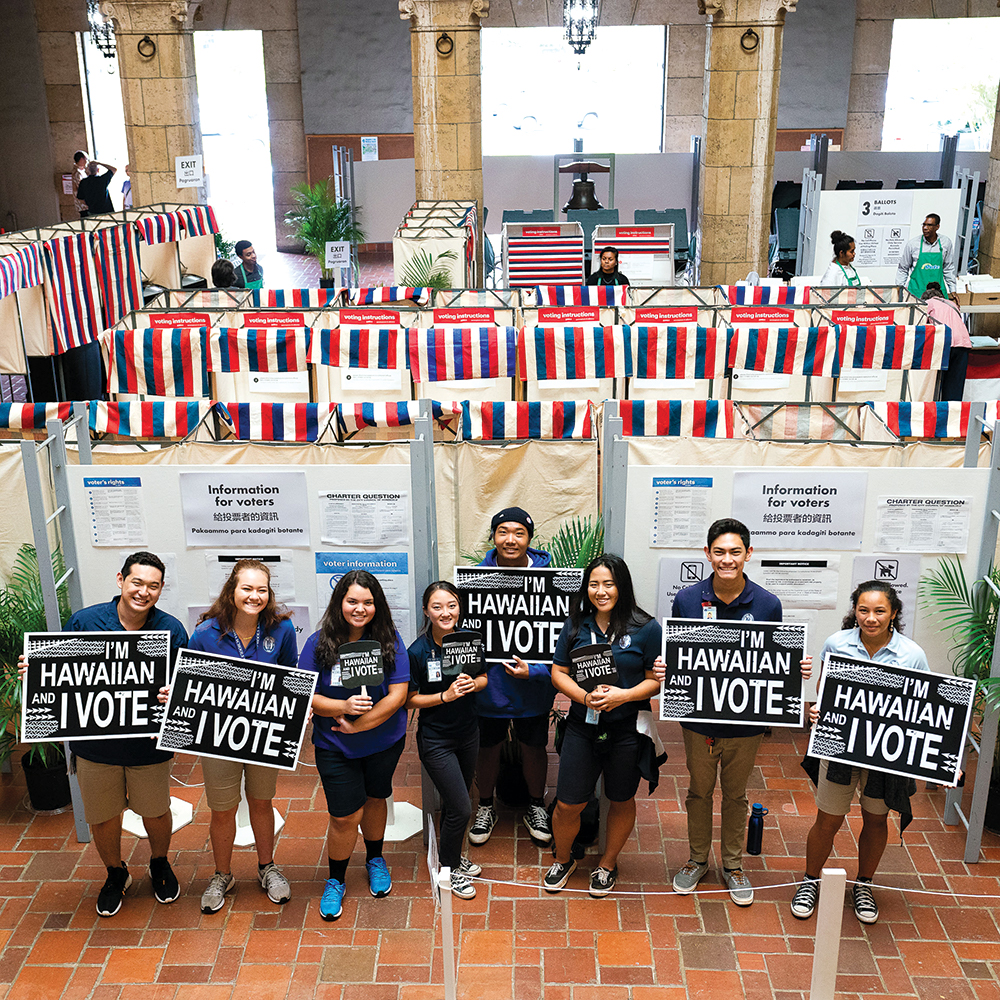

In 2018, students at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama organized a field trip to cast ballots at Honolulu Hale during the early voting period. Kau‘i Burgess, director of community and government relations, says eight seniors participated.

Senior Lucy Lee, one of the organizers, says she and another student were partly driven to organize it after thinking about how some students don’t vote because the polls are closed when they get home to the west side or the North Shore. If students start voting at 18, it will likely become a lifelong habit, she says: “We need to realize that change is happening sooner than we believe and that if we want to be part of it, we need to hop on it now.”

These first-time voters – eight seniors from Kamehameha School’s Kapālama campus – went together to Honolulu Hale to vote during 2018’s early voting period. | Photo: Courtesy of Kamehameha Schools – Kapālama, Kau‘i Burgess

John Hart, political analyst and professor of communication at Hawai‘i Pacific University, says one reason some young adults don’t vote is because civics education is lacking. “We don’t teach students about government, about voting, about any of that, so why do we automatically expect them as an adult to vote?” he asks.

State Rep. Amy Perruso, who has taught social studies at Mililani High School for the past 14 years, says civics education – as well as social studies overall – took a hit under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Federal mandates under this act caused schools to focus time and resources on teaching math and language arts – the subjects that would be tested.

Hart thinks enhanced civics education is the best bet to increase Hawai‘i’s voter participation. Colin Moore says every graduate of a public four-year university in Hawai‘i should be required to take a Hawai‘i politics or general civics class. Public high school students are currently required to take a class called Participation in a Democracy, which focuses on civic engagement, to graduate, plus other social studies classes that teach them about how government works.

Hart is involved with a voluntary national program called We the People, which teaches upper elementary, middle and high school students about the history and principles of the American political system. The program’s culminating activity is a simulated congressional hearing where students demonstrate what they’ve learned in front of a panel of experts who act as judges.

Matt Mattice, state coordinator for We the People and executive director of the King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center, says that since 1999, the center has provided free training and curricula to 414 teachers who have instructed an estimated 36,900 students. He says the effort has made students much more aware of the importance of civic participation.

“These students are informed and they’re going to go vote,” Hart says. “And I don’t see why that program or a program like it couldn’t be made mandatory.”

Native Hawaiian Programs

Census data does not reveal whether Native Hawaiians vote at a lower rate than other groups in Hawai‘i. There is a perception that Native Hawaiians vote at lower rates than the general public, says Joe Kūhiō Lewis, CEO of the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement, but he doesn’t believe it to be true.

While Hawaiian voters are not that different from the general public, he says, they have fewer incentives to vote. Not many Hawaiians run for office, he says, and he doesn’t see many candidates speaking to a Hawaiian demographic. More Native Hawaiians might vote if more Native Hawaiians ran for public office, because that could inspire their sense of pride. He specifically cited Native Hawaiian state Sen. Kaiali‘i Kahele, who this year announced he is running for the congressional seat held by U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard. He adds many Native Hawaiians don’t feel like their votes matter for Office of Hawaiian Affairs elections because they make up a minority of voters – any resident can vote in OHA elections.

In 2018, the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement ran a “I’m Hawaiian and I Vote” campaign to civically and politically engage Native Hawaiian residents. “It was becoming all too regular to hear legislators or elected leaders say, ‘Hawaiians don’t vote,’ ” he says, adding that the campaign was part of the council’s broader efforts to target Native Hawaiian, Asian American and other Pacific Islander communities.

During the primary and general elections, CNHA made over 35,000 phone calls, sent out nearly 9,000 mailers, partnered with Lyft to offer free rides to the polls, held events and registered 1,500 new voters. In addition, the council gave almost $100,000 to member organizations to promote voting. The idea, Lewis says, was to create hype about voting in the hope that more people would cast ballots.

HOW YOU CAN VOTE IN THE NEXT ELECTION

Any person who is 18 or older, a citizen of the U.S. and a resident of the state of Hawai‘i can register to vote here. Registration can be done in person, by mail or online. For more information, click here.

Voter registration deadlines for applications submitted online, by mail and in person:

Primary: July 9, 2020

General: Oct. 5, 2020

Hawai‘i also has same-day voter registration; go to your neighborhood’s polling place to register.

Election Day

• Primary: Aug. 8, 2020

• General: Nov. 3, 2020

Other Solutions

Shirlene Ostrov, chairwoman of the Republican Party of Hawaii, offers another solution to low voter turnout: “The same party in Hawai‘i wins over and over, so most people go, ‘Why do I vote? Why would I vote? It’s going to be the same party, same thing. This is the usual. And we haven’t seen a change from the parties.’ … We have to tell people that they can make a difference.”

Several other sources agree that Hawai‘i needs more competition in its elections. Mason, of the League of Women Voters, says voters deserve more information on candidates’ positions and fewer personal attacks by the candidates.

Lewis of the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement says: “I think because Hawai‘i is so Democratic it works against us. There’s no democracy. After the primary, you know who’s going to be your governor, you know who’s going to be your representative. There’s not much to look forward to in the general election. So we have to almost create competition to motivate voters to engage.”

He says that the Republican Party of Hawaii’s efforts to become more well-known as the Party of Kūhiō might be an incentive for some to vote. A lot of Hawaiians respect what Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole did in terms of leading the passage of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act and the creation of the Hawaiian civic clubs, he says: “Creating some buzz is really important because this is a one colored state where everybody is blue over here.”

Hart raises another question: If people don’t want to vote, do we still want them to vote? If people aren’t informed, he says, “Do we really want to say, well, ‘We’re going to put it on an app, so you can watch it in between the commercials of your sporting event?’ There is that presumption that maybe, why make it too easy?”

UH Mānoa professor Colin Moore disagrees and says people should still vote because in the process of doing so, they learn things – and a democracy should want as many voices as possible.

“We want everyone to vote,” he says. “If everyone voted, what would happen is we would have an electorate that is more representative of the poor, more representative of minorities here that don’t vote as often, more Pacific Islanders, more Filipinos. That voice would grow, and I think that would lead to better public policy.”