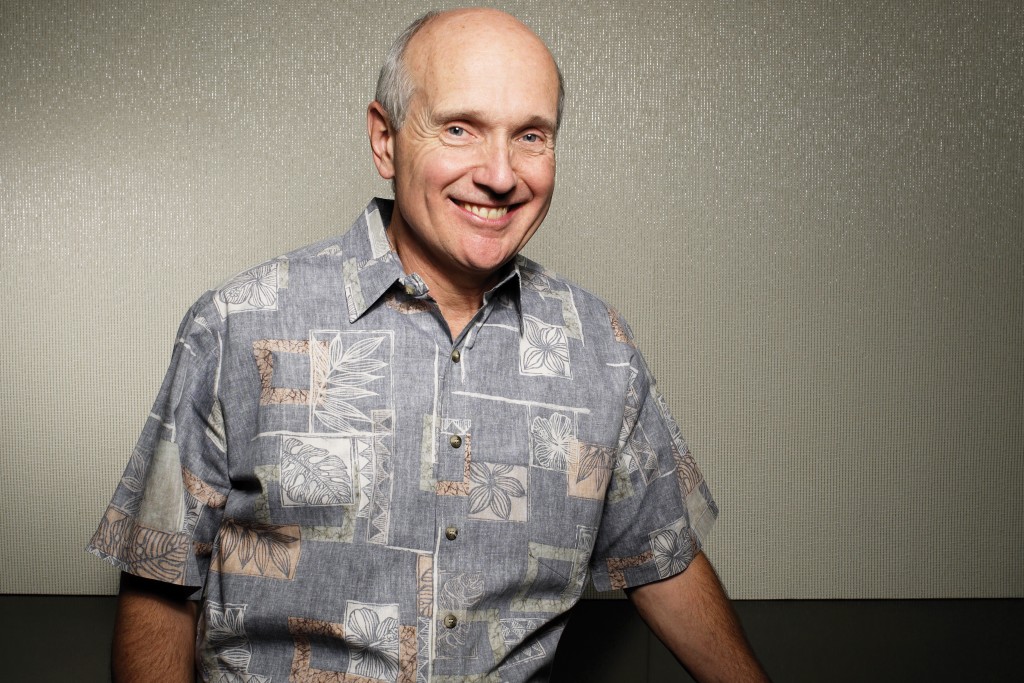

Hawaii Business 2012 CEO of the Year: John Dean of Central Pacific Bank

The toughest challenge was recapitalizing the bank,” says John Dean, Central Pacific Bank’s soft-spoken CEO.

Dean, who came out of retirement in 2010 to help save the struggling community bank, knew what he was getting into. This was his fifth bank and his fourth turnaround as a CEO, so he was keenly aware of how much money he had to raise and how bad the timing was.

“If you look at the goodwill write-off,” he says, “we had over $700 million in losses, so we were running out of capital. And, if you remember, there were a lot of people chasing capital at that time. So, the toughest thing for me was to get investors to believe our vision that, with $325 million, we could return the bank to profitability.”

That’s exactly what Dean and his team did. In a series of road trips and Byzantine negotiations during the spring and summer of 2010, they persuaded dozens of institutional investors not only to buy into Dean’s vision, but to do it on terms that met the elaborate requirements of federal regulators and preserved the bank’s core values. The result was one of the most convoluted business deals in Hawaii history.

“It was probably the most complex transaction I’ve ever worked on,” Dean says. “That’s because there were so many parties involved and everything had to come together just right.”

The story of that transaction, and its enduring impact on Hawaii, is the reason John Dean is Hawaii Business’ 2012 CEO of the Year. Before we tell that story, you’ll need some background.

In order to grasp the extent of what he did at Central Pacific, you have to understand just how improbable it was for a troubled, relatively small community bank in Hawaii to find a leader as experienced and highly regarded as Dean. He had already turned around four banks on the mainland. At his last, Silicon Valley Bank in California, he came into an institution that, much like CPB, was under a regulatory order and wallowing in losses. After restructuring, Dean and the investors rode the tech boom of the 1990s, and Silicon Valley Bank’s market capitalization grew from $60 million to $3 billion. That’s a deal people remember.

After Silicon Valley Bank, Dean went into semiretirement, founding Startup Capital Ventures, a successful venture-capital firm that specialized in smaller tech startups, some of them in Hawaii.

When CPB found Dean, he had been living part time in Waimanalo since 1993. In fact, although most of his professional career was spent on the mainland, he had strong ties to Hawaii and the Pacific. As a young man, he served in the Peace Corps in Western Samoa, where he met his wife, Sue, who was also a Peace Corps volunteer. After their tour in Samoa was over, they spent time in Hawaii and developed a love for the Islands. After they bought their Waimanalo home, they tried to spend about 20 percent of their time there, which became easier when Dean retired from Silicon Valley in 2003. Since then, the Deans have become deeply involved in the philanthropic community in Hawaii. They donated $250,000 to sponsor a scholarship at the University of Hawaii’s Shidler College of Business; they established a nonprofit called the Entrepreneurs Foundation of Hawaii; and they sponsor a math program at Waimanalo Elementary School.

It’s easy to see why Central Pacific wanted Dean; it’s harder to see why he left retirement to save the bank. It wasn’t for money. In his first year at CPB, he drew a salary of $1. He dedicated most of his stock options to the bank’s new charitable foundation. And, even though he began to draw a salary in 2011, he’s been busy giving it away to organizations like Catholic Charities and the Aloha United Way, where he’s chair of the 2012 campaign.

Catherine Ngo, the bank’s chief administrative officer, has been with Dean longer than anyone else at the bank. One of a handful of executive staff members he brought to Central Pacific, she’s worked for Dean for more than 20 years, first at Silicon Valley Bank, then as a partner at Startup Capital Ventures. She says she was surprised that he took the CPB job.

“I knew that people had approached him about the position. But I also know that he was at a point in his life where he was quite satisfied. He had a nice balance of work and time to spend with his family. I know what he was trying to do was help them find good candidates. He introduced the board members to people he knew in the banking community. I think the board actually met with a couple of candidates, but Crystal Rose, who is chair of the board, and the other board members saw that John was clearly the strongest and best fit for the bank.”

Ngo also helps explain why Dean eventually said yes. “There were several quarters of significant losses. I think potential failure was staring us in the face. But John has always been up for a good challenge. In that sense, it didn’t really surprise me.”

For his part, Dean says if you had asked him three weeks earlier if he would ever come out of retirement to work at another bank, he would have said, “Never.” He says his wife is the reason he took the job. “I talked to Sue, and she said, ‘How many employees are there?’ And I said about a thousand. And she said, ‘What happens if the bank doesn’t make it?’ And I said, ‘Unfortunately, most of them are going to end up on the street.’ And Sue said, ‘Then you’ve got to go do it.’ ”

Great Culture

Although Central Pacific’s financial troubles were serious, the bank still had a healthy culture. “This is the big surprise,” Dean says. “Of all the struggling institutions that I’ve gone to, oftentimes, they lose their values in the struggle to survive. But this bank had a strong set of values prior to my arrival. I think it’s important that message get out. And what’s nice is that those values complement what I believe. I think the only thing I had to do was clarify those values.”

Dean emphasizes that a company’s values have to be reflected in its business operations. “While it was a great culture, good from an integrity and ethical point of view, there was more of a silo approach in the company: ‘You have your area, I have my area, and we’re not necessarily going to work together.’ So, we’ve really pushed teamwork – not just within the functional areas, but across the institution. So, if you’re a client, we need everyone in the bank pulling together to provide you exceptional service.”

To encourage that, Dean established a group – below the executive committee – to identify the bank’s core values in a way employees could remember and apply. They came up with T.I.E.S – Teamwork, Integrity and Excellent Service to customers. Then Dean introduced several programs that recognize employees who embody the company values. VP Norman Nakasone, who manages the service quality department and is the person Dean calls “the heart and soul of CPB values,” explains how the programs work.

The “On-the-Spot Rewards” card, he says, is a simple way for employees to recognize other employees who do something that embodies the core values. The card, which has a scratch-off section, sometimes comes with a small prize, like a $10 gift card. The recipient also qualifies for a monthly drawing. “Since we launched that program in April,” says Nakasone, “we’ve had 5,000 of these cards come in. The wonderful thing about that is one of our core values is teamwork, and roughly 50 percent of those cards are from an employee in one department to an employee in another department.” It’s a simple way to break down those silos.

Nakasone says another program, called E-Notes, makes it easy for managers to recognize employees who may never see the impact their actions have on customers. Senior VP for community banking Bob Yee gives the example of a newly married customer who needed to close on a real estate transaction quickly to buy a condominium that would accommodate his disabled spouse. Because various departments worked together, Yee says, they were able to book and close the deal on the same day. “I was able to recognize all the departments and the key individuals by submitting an E-Note online, which was published within the week for the entire company to see. Without E-Notes, these people may not have been recognized or seen the ultimate impact on the customer, who, needless to say, was extremely happy.”

In all, Dean introduced more than a dozen programs to promote core values and improve communication in the bank. Maybe the most far-reaching has been the installation of upstream evaluations. According to Yee, when the upstream review policy launched, it started at the top. “John asked his direct reports to do an upstream appraisal of him first,” Yee says. “Then it was cascaded down to the various levels. Now, after a couple of years, it’s gotten to the point where staff are doing upstream appraisals of branch managers. And, of course, the branch managers are doing an upstream appraisal of me. So, line managers are getting honest, open feedback from the tellers on the line. If you’ve been a manager for 40 years, that can be an eye-opener.”

Dean’s willingness to “walk the talk” has been noticed by employees. Almost everyone at the bank offers examples of small acts in which he’s shown character, humility and wisdom. “This ID badge is a perfect example,” says Nakasone, waving his CPB lanyard. “All employees are required to wear this ID badge in order to access their particular section of the building. John Dean is someone who, even at the level he’s at, wears his ID on a lanyard like everybody else. I’ve never worked for another CEO who did that.”

When low-key Dean participated in a flash mob dance for a company video, dressing in disco clothes a la Saturday Night Fever and throwing in a few John Travolta moves, several managers were surprised. “At first, guys like us were apprehensive,” says John Taira, senior VP for commercial banking. “It’s embarrassing to dance in front of other people. But it was a great morale enhancer for the bank.”

Because of that mix of character, knowledge and success, Dean inspires great loyalty in his employees. “I’ve known him for so many years,” Ngo says. “I’d follow him into any organization, even if it meant walking over hot coals to get there. And after I came here, there were a number of colleagues from Silicon Valley Bank who called and wanted to be part of this organization. That’s the kind of leader John is.”

“It’s just been a great opportunity working alongside John,” says David Morimoto, senior VP and treasurer for the bank. “It’s only been a couple of years, but he’s the closest thing to a real leader I’ve been involved with. I just want to be a sponge; I want to absorb as much as I can. Every day, it seems he’s still learning how to be a better leader. Even though he’s been the CEO of five companies and he’s close to the end of his career, he doesn’t think he knows it all.”

Taira is succinct: “He makes me want to be a better person.”

The Big Deal

In the end, though, integrity only gets you so far. As Dean puts it, “Values are important here and we spend time on them, but core values, by themselves, would not have turned this bank around. There were so many things done from a purely business point of view – in terms of the capital markets, in terms of fundraising, in terms of the hard decisions we made – that were critical.”

Hard decisions included across-the-board expense cuts and a 10 percent reduction in force (conducted mostly by attrition and hiring freezes). It meant having high expectations and holding employees to those expectations. But the most important decisions were those that led to the recapitalization of the bank.

“It was all very complicated,” says Dean. “For example, we had a tax-loss carry-forward worth about $175 million. That means those losses could be used against future earnings. But, if the deal wasn’t structured appropriately, based on rules set by the FASB and SEC (the private sector’s Financial Accounting Standards Board and the federal government’s Securities and Exchange Commission), we would lose that tax-loss carry-forward. On top of that, we had the Federal Reserve’s holding-company regulations, which said nobody can own more than 24.9 percent of the company or they become part of the Bank Holding Company Act. Long story short, the structure was we did two 24.9s (The Carlyle Group and Anchorage Capital Group), and everyone else, to preserve the deferred tax asset – the DTA – had to be 4.9 percent or less.” In other words, there were a lot of people involved, and the size of their investments had to be strictly managed.

That’s complicated enough, but because the bank also received $135 million in bailout money from TARP – the Troubled Assets Relief Program – it had to negotiate a deal with the U.S. Treasury. That $135 million was secured with preferred stock, which would have made Treasury debt senior to any new investments. Naturally, the equity capital guys didn’t want to use their investment to make the Treasury whole, so the bank had to persuade the Treasury to convert its preferred stock to common stock. That meant the Treasury had to agree to take a $63 million loss.

The transaction Dean concocted included $10 million in employee stock options and a $20 million rights offering, which gave legacy investors the opportunity to buy stock at the same price as the equity investors. He even got the new investors to contribute to charity. “Please note,” Dean says, “we contributed $8.2 million to the Central Pacific Foundation last year. Think about that for a minute. These are private-equity investors that are all driven by bottom-line earnings. But I went and talked to them about it, and they said, ‘No, giving back to the community is important. We understand that.’ So, what I’d like to say is I think we ended up with some very good investors.”

The question, of course, is how was Dean able to strike a deal with investors when his predecessors weren’t? Previous CPB executives made several road trips from the summer of 2008 to the fall of 2009, pitching mainland investors on the investment opportunity at the bank. But no one bit. Morimoto, who as bank treasurer was part of the road shows under both Dean and his predecessors, says a big part of the answer is Dean’s reputation from Silicon Valley Bank.

“It was a remarkable run,” Morimoto says. “A lot of investors made a ton of money at Silicon Valley Bank during that period. So, when we went out with John for capital, we crossed paths with a lot of people where almost the first sentence out of their mouths was, ‘I know you; I invested at Silicon Valley.’ How’s that for a door-opener?”

Wayne Kirihara, the bank’s chief marketing officer, got another look at what Dean’s reputation could do. “The day John first came aboard, I was on the phone with the regulator. I asked them, ‘Can we please make some kind of announcement that John Dean is our new CEO, subject to regulatory approval?’ Normally, that kind of request takes 30 to 60 days to approve, but the regulator just said, ‘John Dean! Go ahead and announce it.’ I just about fell out of my chair.”

More than needed

Morimoto, while careful not to criticize prior CPB leadership, highlights the contrast between his road trips before Dean and with him. “It went a lot better with John,” Morimoto says. “We generated a lot of interest. Whereas previously I think we were only able to get two firms to even take a look at the company, with John, I think we had eight or 10 companies take a deeper look. And ultimately we got four term sheets to be our lead investors. In the structure that we needed to get CPB recapitalized, we only needed two lead investors. It’s our understanding from Sandler O’Neill, our investment banker, we were the first troubled recap to have more term sheets than we needed.”

That meant John Dean and the bank had some leverage, which would be critical as they negotiated the terms of the deal. “It allowed us to pick who we wanted to partner with,” Morimoto says. “Some of the people who wanted to invest in us may have had different game plans than we did. For example, they may have wanted to use this as a jumping pad to something more on the West Coast, more of a multistate organization. But John has always wanted to bring things more Hawaii-centric, something along the lines of what Bank of Hawaii did.”

Morimoto also points out that Dean was honest with investors, even when it complicated the transaction. For example, with private equity, the exit strategy for an investment is often through mergers and acquisitions. “The attraction,” Morimoto says, “is that with M&As, you generally get a premium to the market price. But John was very clear he didn’t think this was an M&A exit. He told them, ‘You will probably have to sell your shares back into the open market.’ ”

Of course, it wasn’t just reputation and leverage that made the deal. Faith helped. “We worked hard,” Dean says. “It was sell, sell, sell. But I would also tell you we believed in the story. Everyone there believed that, with the capital, we could make this bank profitable again. These equity capital people look at pitches all day long. If you’re not passionate, if you don’t believe what you’re saying, forget it.”

John Dean timeline

Dean was born in Lawrence, Mass., on August 14, 1947. He graduated from Holy Cross College in Worcester, Mass., and received his MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

Photos courtesy of the Dean family

Dean at 9 months old.

Graduation picture from St. Mary’s of Redford High School in Detroit in 1965.

Dean and his wife, Sue, return from their Peace Corps duty in Westerm Samoa, via Rio de Janeiro, in 1972.

The Deans with their daughters, Monica and Sally, when they lived in Texas.

The Dean family on an Alaskan cruise in 2005. Left to right, Sue, Monica, Sally and John.

Interviewed in September by Susan Yamada at the Shidler College of Business’ Kipapa i ke Ala lecture series, which John founded and sponsored.

“Cupcake Wars,” a fundraiser for Aloha United Way.

Dean with his mother, Monica Dean, at her 90th birthday celebration in October.